This is a comprehensive long guide covering all Made in Italy cashmere brands in the Brands series, organized by history, characteristics, quality, and price range. Section 01 briefly reviews cashmere's development over the past two millennia—from its origins in Central Asia and Tibet before the 17th century, to the pivotal shift centered in Britain during the 18th and 19th centuries, and finally to Italy's comprehensive rise in brand development and fabric craftsmanship during the 20th century.

Italian cashmere brands are primarily concentrated in two regions: the Valsesia mountain area northwest of Milan, and the Umbria region in central Italy. These spring months of April and May offer pleasant weather and verdant scenery, making it an ideal time to visit these production areas—friends in the industry might consider an Italian cashmere tour.

I use medium-thickness 100% cashmere long-sleeve sweaters (those with noticeable thickness that can be worn as outerwear in spring and autumn) as a price benchmark, categorizing brands according to the article's section outline:

02|Top-tier Cashmere Brands ($2,000–4,000)

Distinguished by premium fabrics or excellence in dyeing, craftsmanship, fit, and brand strength. Representative brands: Loro Piana, Lanificio Colombo, Brunello Cucinelli

03|Upper-mid Range Cashmere Brands ($1,000–1,800)

Slightly less influential than top-tier brands, but still excellent in fabric quality, details, and fit. Some brands have already established pricing power. Representative brands: Sa Su Phi, Agnona, Malo

04|Mass Market High-value Brands ($600–800)

Most are priced under 5,000 yuan when converted to RMB. Most brands in this category don't design or produce the medium-thickness outerwear I mentioned, or if they do, they're typically cardigans. They mainly focus on lightweight base layers in the $200–500 range. This category balances price, fit, and cashmere quality with good brand selection options. While not top-tier, they're excellent enough for most people. Mostly thin styles with fewer substantial pieces, suitable as basics. Representative brands (in order of overall quality from high to low): Piacenza 1733, Drumohr, Mauro Ottaviani, Cruciani, André Maurice, Neri Firenze

The brands I dislike are mostly in this category. Brands at this price point, whether Chinese or Italian, tend to be inconsistent and face development challenges due to high competition, small profit margins, and the need to balance quality with marketing. Many that abandon quality standards slide into the category of brands I don't recommend.

05|4 Italian Brands Not Recommended

Many operate under Italian names but aren't actually manufactured in Italy. Some specific product lines may be acceptable, but overall they're not worth recommending and serve as negative examples.

06|Cashmere Fabric Supplier Brands

Focused on supplying high-end cashmere fabrics rather than designing ready-to-wear clothing. Representative brands: Loro Piana, Lanificio Colombo, Cariaggi, Botto Giuseppe, Piacenza 1733

Overall, we prefer brands in the first and second tiers, while third-tier brands (such as those in category 04) are more suitable as basics for layering. Except for Loro Piana and Brunello Cucinelli (which will be covered separately later due to their large scale, numerous collections, and abundant information), we've already provided detailed introductions to all other brands in our Brands series—click the green text to read these articles. This compilation only briefly highlights each brand's main characteristics.

Besides cashmere, many of these brands also offer wool knitwear, with summer collections typically featuring linen, silk, and cotton—all natural fibers. I initially fell into the cashmere rabbit hole because of my preference for natural fabrics; I never consider polyester, no matter how high-quality, and at most would accept cupro. Some top-tier suit brands and minimalist brands also offer cashmere items but don't particularly emphasize cashmere quality or Italian production. This article focuses specifically on Italian brands with the "Made in Italy" label that specialize in cashmere. Other aspects will be explored in future articles as more experience and material is accumulated.

01

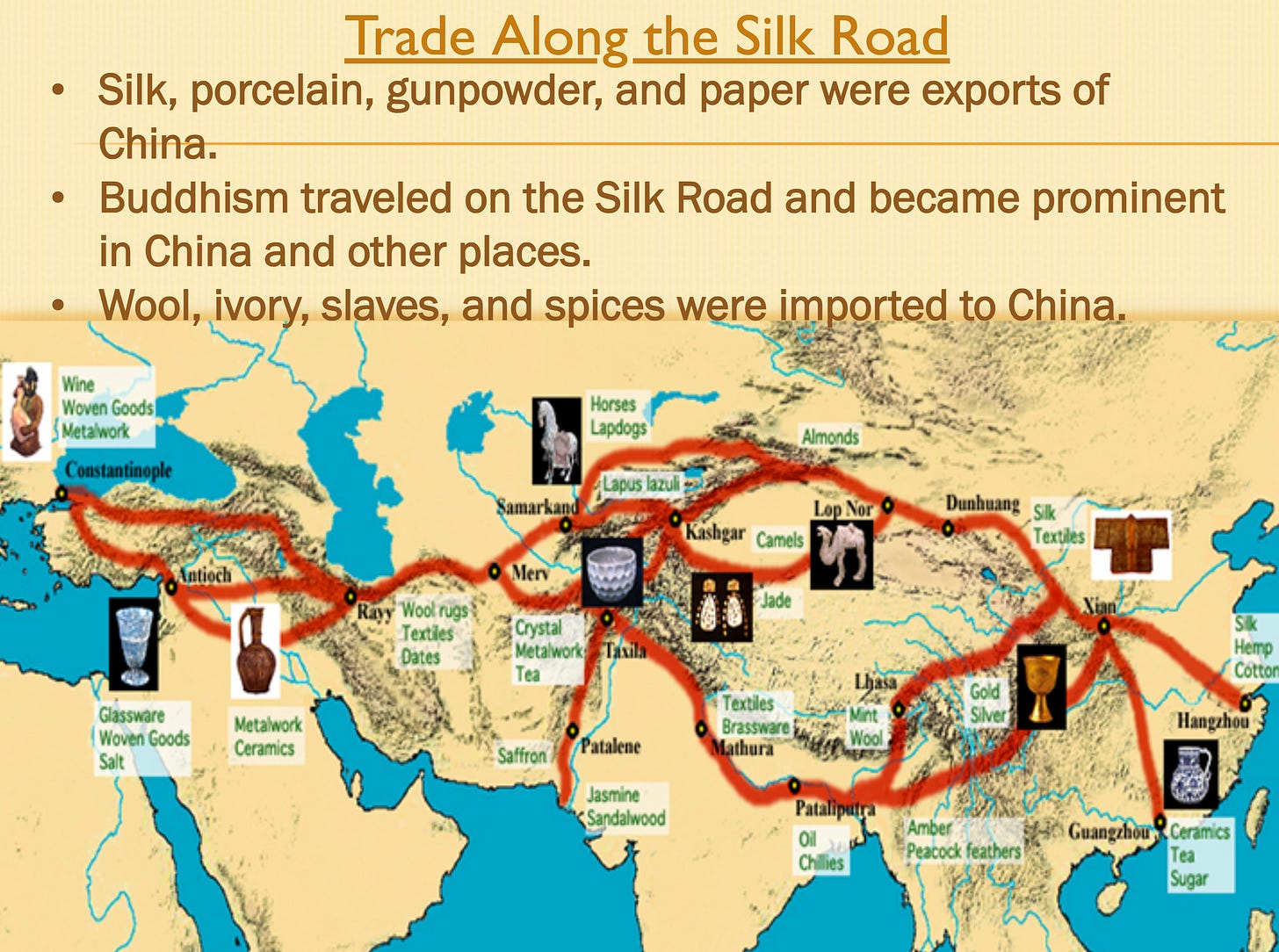

Cashmere scarves were mentioned in Afghan documents and the Bible as early as the 3rd century BCE. Historical records show that Western regions paid tribute to the Han Dynasty with "fine felt" (fine wool textiles), with regions like Wusun and Dayuan primarily trading wool products. Some of this wool was fine wool, or cashmere. Today, some Han Dynasty cashmere products have been excavated in Xinjiang and Ningxia.

During the Song Dynasty, cashmere resources on the Silk Road were mainly found in Western Xia. The Silk Road's path through Ningxia followed the Yuanzhou Xiaoguan Road before the Tang Dynasty, and after the Song Dynasty, it followed the Lingzhou Road centered around today's Lingwu City. By the early Song Dynasty, Lingzhou had become an international transportation hub, trade transit point, and distribution center. Envoys from the north, Western regions, India, and Hexi passed through Lingzhou Road, as did Western monks traveling east to the Song Dynasty and Song envoys heading west to collect Buddhist scriptures. Today, Lingwu is China's high-end cashmere processing center, where the famous Zhongyin Cashmere is located.

The Guge Kingdom of Tibet (Ali region) from the 10th to 17th centuries based its trade with neighboring countries on cashmere, salt, and gold through the highland Silk Road. Many historical records document Tibet as a cashmere production area. I estimate that Tibet and Kashmir regions likely produced cashmere from Tibetan antelopes, while regular goat cashmere came from Inner and Outer Mongolia.

When Venetian merchant Marco Polo visited China via the Silk Road from 1271-1295, he recorded that Mongolians frequently used cashmere and traded it with various countries. During the Yuan Dynasty, Kublai Khan's cashmere entered Western trade networks via the Silk Road and became a luxury item for the Yuan court.

In the early 16th century, Kashmir Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin introduced cashmere shawl-making techniques and encouraged Central Asian craftsmen to settle in Kashmir, promoting the rise of the cashmere industry. Cashmere became Kashmir's main trade item, with these shawls transported by caravans to India and the Middle East.

During this time, the land-based Silk Road was gradually replaced by maritime trade routes. China entered the more autocratic and closed Ming and Qing eras, with foreign trade primarily conducted by sea.

After Britain colonized India and Pakistan in the 18th century, the East India Company, besides collecting spices, cotton, and calico printed fabrics, also gathered cashmere from Central Asia and Afghanistan, bringing it back to Britain where it became beloved by high society.

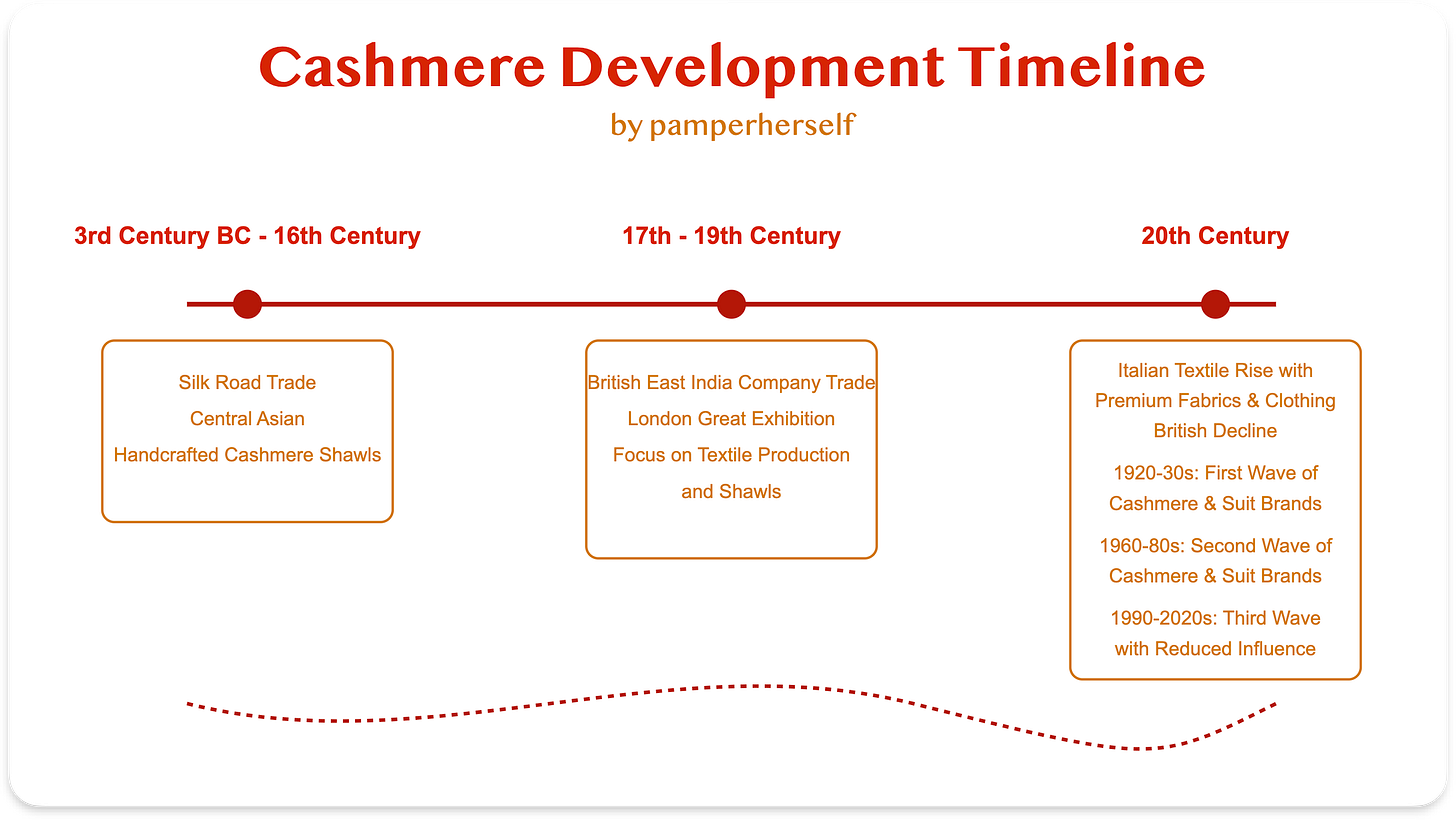

The cashmere products mentioned above were hand-sewn shawls. From the beginning of Britain's First Industrial Revolution in the 18th century until the late 19th century, cashmere production gradually industrialized. In the first half of the 20th century, French haute couture brands emerged, shifting from custom production to ready-to-wear, and cashmere products expanded from scarves to tops, pants, and other categories. By the 1970s, the authority in cashmere shifted from Britain to Italy.

In the late 18th century, Britain's domestic cotton textile industry was stimulated by cheap imported Indian cotton textiles, promoting the First Industrial Revolution. The achievements of this revolution also benefited the wool textile industry, leading to the emergence of textile factories like Johnstons of Elgin, Joshua Ellis, and the predecessor of Drumohr , as well as cotton textile brands like John Smedley. At this time, textile factories specialized in fabric cleaning, dyeing, spinning, weaving, and finishing processes; it would take at least another half-century before they began producing ready-to-wear accessories.

The first Italian company to produce cashmere fabrics was Piacenza 1733. Due to its early establishment during that textile era, the Piacenza family developed a genetic predisposition for textiles. Even today, Piacenza 1733 excels in textile processing and fabrics, though they also produce scarves and clothing.

This historical background explains why British cashmere brands established during this period still emphasize textile production today, unlike the French haute couture brands of the early 20th century that excel in clothing design, or the luxury brand marketing of the late 20th century's era of big capital.

In the 19th century, Empress Josephine, Napoleon Bonaparte's first wife, owned over a hundred cashmere shawls, promoting cashmere as a fabric worthy of nobility and royalty throughout Europe. Textile factories began producing industrialized cashmere scarves.

With the East India Company's continued importation of Indian cashmere and the expansion of cashmere raw material import channels from Tibet, Inner Mongolia, and other parts of China during the mid-19th century Opium Wars, British factories were able to steadily obtain quality raw materials to support the development of emerging industries. During this period, Alpaca wool from Peru was also discovered by the famous Bradford merchant Sir Titus Salt.

The British factory boom further developed in the mid-19th century, with London hosting the Great Exhibition. Wool textile brands like Pringle of Scotland and Drumohr emerged (they participated in this industrial exhibition), along with new cotton textile brands like Sunspel. These British brands established in the 18th and 19th centuries have continued production to this day.

The first large-scale industrial production of cashmere occurred in the mid-19th century. Scottish manufacturer Joseph Dawson improved combing techniques in the late 19th century, significantly increasing cashmere purity and further consolidating Britain's dominant position in the global cashmere industry.

I discovered that London's Burlington Arcade (established in 1819) and Milan's Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II shopping street (built between 1865-1877) both feature the indoor arcade architecture of the Crystal Palace from the 1851 London Great Exhibition—truly witnessing history.

China skipped this era and directly entered the age of department stores and shopping centers suitable for the middle class, with clearly marked prices and return policies, like Le Bon Marché, Harrods, and Saks Fifth Avenue. The earliest in mainland China was Wing On Department Store in Shanghai, established in 1918.

Throughout centuries of European familiarity with cashmere, the concept of cashmere was almost synonymous with Kashmir shawls for a very long time. Cashmere factories that emerged in the mid-to-late 19th century primarily produced cashmere scarves, such as BEGG & CO, founded in Scotland in 1860. Johnstons of Elgin and Joshua Ellis, established in the late 18th century, also began making cashmere scarves. Pringle of Scotland expanded from knitted socks to cashmere sweaters, making cashmere knitwear increasingly common.

The Italian wool and cashmere factory Botto Giuseppe , founded in the latter half of the 18th century, also bears the era's imprint of knitting production. Like Piacenza, it still focuses on processing and fabric trading today, without expanding into ready-to-wear clothing—offering only the cashmere scarves that became popular to produce in the mid-to-late 19th century.

Below is John Singer Sargent's "Cashmere" painting from 1908, part of Bill Gates' collection.

In the early 20th century (1910s-1930s) before the World Wars, Paris haute couture women's brands like Chanel began using Le Kasha cashmere. New British cashmere brands such as Ballantyne and N.Peal also emerged during this period. By this time, British wool and cashmere factories had begun to decline, experiencing a brief revival during the 1930s-60s due to the fashion influence of the Prince of Wales (Duke of Windsor), but the overall trend was still downward with diminishing momentum. During this phase, the Italian textile industry began its rise.

The 1930s saw the establishment of Loro Piana, Zegna, and top-tier tailoring brands mentioned in 17 Top Luxury Men's Suit Brands for Gentlemen like Cesare Attolini, Brioni, and Isaia. The second wave came in the 1960s-80s, when mid-to-high-end cashmere brands such as Brunello Cucinelli, Agnona, Malo, and Fabiana Filippi were established. Suit brands from this period included Kiton, Stefano Ricci, and Giorgio Armani. The third wave consisted of Italian cashmere brands created from the 1990s-2010s, though their development momentum was somewhat weaker compared to the previous two phases.

This section of cashmere development history can be simply organized with this chart:

Cashmere gained widespread global sales after the 1960s in Italy. Most of the Italian cashmere brands introduced in this article were established during this era, and even those founded in the first half of the 20th century only began to develop steadily from the 1970s onward due to the impact of World War II. Besides cashmere brands, the suit brands with decades of history that I've written about also developed in the 1960s, with Akris being a typical example. The period from the 1990s to 2020s marked the development era for emerging quiet luxury minimalist brands.

02

Loro Piana

Loro Piana's heavyweight or intricately crafted cashmere coats, sweaters, and core fabrics like Storm System®, Baby Cashmere, and The Gift of Kings® are all Made in Italy.

However, their wool, linen, silk, and some ordinary cashmere fabrics are not Made in Italy. For the two items below, Loro Piana's official website doesn't specify their country of origin. Loro Piana also has two types of stores: shops like the one in Beijing's WF Central mostly carry mid-to-low-end goods from unspecified origins without core collections—hardly anything appealing. The high-end goods are only available at locations like SKP.

Before LVMH acquired Loro Piana in 2013, only old money elites bought from them. After the acquisition, LVMH began promoting cashmere brands the way they had previously hyped LV and Dior. This raised awareness not only for Loro Piana but for other cashmere brands as well, making Chinese consumers increasingly willing to pay for cashmere brands.

What's been heavily promoted is Loro Piana's soft and tender Baby Cashmere. Previously, Chinese brands like Erdos focused on sturdy, durable cashmere yarn, but since then have pursued softer textures. Ordinary brands that can't source such high-quality cashmere fabrics resort to technological tricks like adding silicone oil and extra fluffing to make their products softer, which actually reduces the quality and longevity of the cashmere.

You may notice that I typically write about more niche brands. I'm quite averse to heavily capitalized brands like Loro Piana with their excessive marketing premiums and exaggerated claims (even mysteriously hyping lotus fiber). Their store sales staff are particularly cold, embodying strong capitalist exploitation characteristics. That's why I initially preferred visiting Brunello Cucinelli stores and became a fan—their sales staff are more personable, and the brand maintains humanity while pursuing capitalization.

However, setting aside all the capital-driven aspects beyond the fabric itself, Loro Piana's core collection cashmere quality is undeniably the best. If you find good outlet discounts or have plenty of money, you can choose their Made in Italy core collections: Baby Cashmere (average diameter 13.5 microns) for knitwear, Storm System® for trench coats and overcoats, The Gift of Kings® (12-micron merino wool) for wool items, and select pieces with the most complex textures and substantial thickness. Their top-tier vicuña fabric is also worth investing in.

Loro Piana has various other collections, but I only recommend the four mentioned above, as they're specifically highlighted in Loro Piana's official "Excellence" section.

For Loro Piana's non-core collections, you can consider many other mid-to-high-end brand alternatives. With any brand, only choose their core collections. By selecting core collections from each brand, your wardrobe will not only be high quality but also diverse. Unfortunately, most consumers who aren't particular about clothing or daily details only know what marketing capital promotes, lacking the initiative to explore independently—they're naively extravagant and deserve to pay the premium.

Before Loro Piana became popular in China, many Middle Eastern and Russian wealthy customers purchased from them, which influenced their fit—waists tend to be quite loose (humorously, Loro Piana pairs well with "Shanghai money").

Brunello Cucinelli

If you find Loro Piana's designs too ordinary, consider Brunello Cucinelli. The two brands' cashmere differs—Brunello Cucinelli's cashmere isn't as fine or soft as Loro Piana's, but has better flatness and thickness, with many heavyweight cashmere sweaters. I've already compiled their lookbook and core collections in Brunello Cucinelli: 10 Representative Items—check that article for detailed images. Here I'll just briefly mention them.

BC's core menswear: Prince of Wales check and pinstripe suits, corduroy series, cashmere down vests, shearling jackets and coats, turtleneck cashmere sweaters and crew neck cardigans. BC's signature men's footwear includes boots, loafers, and sneakers.

BC's core womenswear: Any shoes, boots, pants, suits, or cashmere sweaters with Monili beading or sequins, BC's signature top-heavy/slim-bottom pants, mesh cashmere and linen shirts, and shearling coats and jackets.

Brunello Cucinelli's women's style embodies a powerful feminine aesthetic, somewhat like a high-end version of Ralph Lauren's model quality—instantly recognizable old money elegance.

Like Loro Piana, Brunello Cucinelli also has outlet stores, typically offering 50-60% discounts. Events like next month's anniversary sale at Beijing Badaling Outlets are worth checking out. Since their marketing isn't as intense as Loro Piana's, there's less competition for merchandise. They also collaborate frequently with Lane Crawford, offering more purchasing channels.

Lanificio Colombo

Like Loro Piana, Lanificio Colombo excels in fabrics and is a top-tier fabric supplier. They offer vicuña and distinguish between Made in Italy and other versions (with "other" often meaning Made in China due to their relationship with Chinese distributors).

As I discussed in my Lanificio Colombo article, their fit and design experience doesn't match the two brands above. The brand prioritizes its fabric supply business, providing cashmere fabrics to major French luxury brands (Hermès , LV, Dior). Max Mara's wave-pattern cashmere fabric comes from them. Since their strength lies purely in fabrics, I only recommend purchasing items where fit isn't crucial: cashmere base layers, scarves, and ponchos. For menswear, jackets are worth considering.

Comparatively, Lanificio Colombo isn't as well-known as the brands above. In China, they're operated by the same company as Giada, making them adept at Chinese-style Italian marketing with strong capitalist attributes. Be mindful when purchasing in China. Most cashmere shoppers would prefer Brunello Cucinelli or Loro Piana over Colombo.

I'll cover this brand again in section 06 on cashmere fabric suppliers—there's not much to say about their ready-to-wear clothing.

03

This category also includes Fabiana Filippi , but I've already written about them in detail in that Brand story—how after being sold to the Prada group, they transformed into a quiet luxury minimalist brand more similar to Jil Sander.

Cashmere brands in this price range, being already mid-to-high-end, can easily get acquired by fashion conglomerates if the founding families don't push hard enough to reach the top tier.

Brands in this series like Agnona and Malo have been bought and sold multiple times, with creative directors changing frequently, though they've fortunately maintained their cashmere DNA. Fabiana Filippi's cashmere has been replaced with wool, and natural fabrics have been swapped for synthetic fibers since being sold 3 years ago. Even their previous years' cashmere inventory has disappeared from the market, so I'm not recommending this brand in this compilation, though it was truly an excellent brand before—unfortunately, the founder was too laid-back.

These mid-to-high-end cashmere brands in part 03 are my favorites—hidden gem cashmere brands that not only feature excellent fabrics but also great fit, detailed craftsmanship, and unique colors with sophisticated dyeing techniques.

Agnona

I've written two articles on Agnona: one focusing on the Brand story and cashmere and another concentrating on men's and women's pants and creative director changes.

Agnona has been unstable in recent years since Zegna sold it to his son-in-law in 2021 and added a men's line. The women's design quality has noticeably declined, with less heavyweight cashmere fabric and increasingly thinner materials. Their previous cashmere runway shows have also been canceled. As the men's line is just starting, much attention is focused there, with prices slightly lower than women's wear. In the first few years, many women's designs leaned toward menswear.

With careful selection, you can still find one or two good pieces. Although fabric quality has decreased, their clothing fit and design have remained consistent.

Agnona's womenswear isn't as aggressive as Brunello Cucinelli's—it's cleaner and more balanced, with colors primarily in white, beige, and light shades. Agnona's menswear is better suited for slimmer, younger men, somewhat resembling Zegna, ideal for young second-generation wealthy individuals. It's similar to The Row Menswear, with Sunspelbeing an affordable alternative.

Below is Agnona's women's wear for SS 2025. After the new creative director took over, the spring/summer collections have performed better than fall/winter.

The colors are sophisticated—the previous creative director paid great attention to natural colors, and the new generation maintains Agnona's sophisticated color sense.

If Agnona continues to develop and stabilize over the next few years, it will be excellent. Currently in China, the only purchasing channel is SKP, and it's unstable. There's little content on Chinese social media and minimal systematic promotion, making it more suitable to visit in Milan. After buying those wide-leg pants, I've become a fan of this brand—I like both the men's and women's wear, suitable for both of us. I hope the fall/winter cashmere collection will continue to improve under the new leadership.

Though the Zegna Group is also big capital, it's different from French conglomerates—they emphasize fabrics and social responsibility, with more old money taste. Since they started with menswear, they tend to be more grounded in that area.

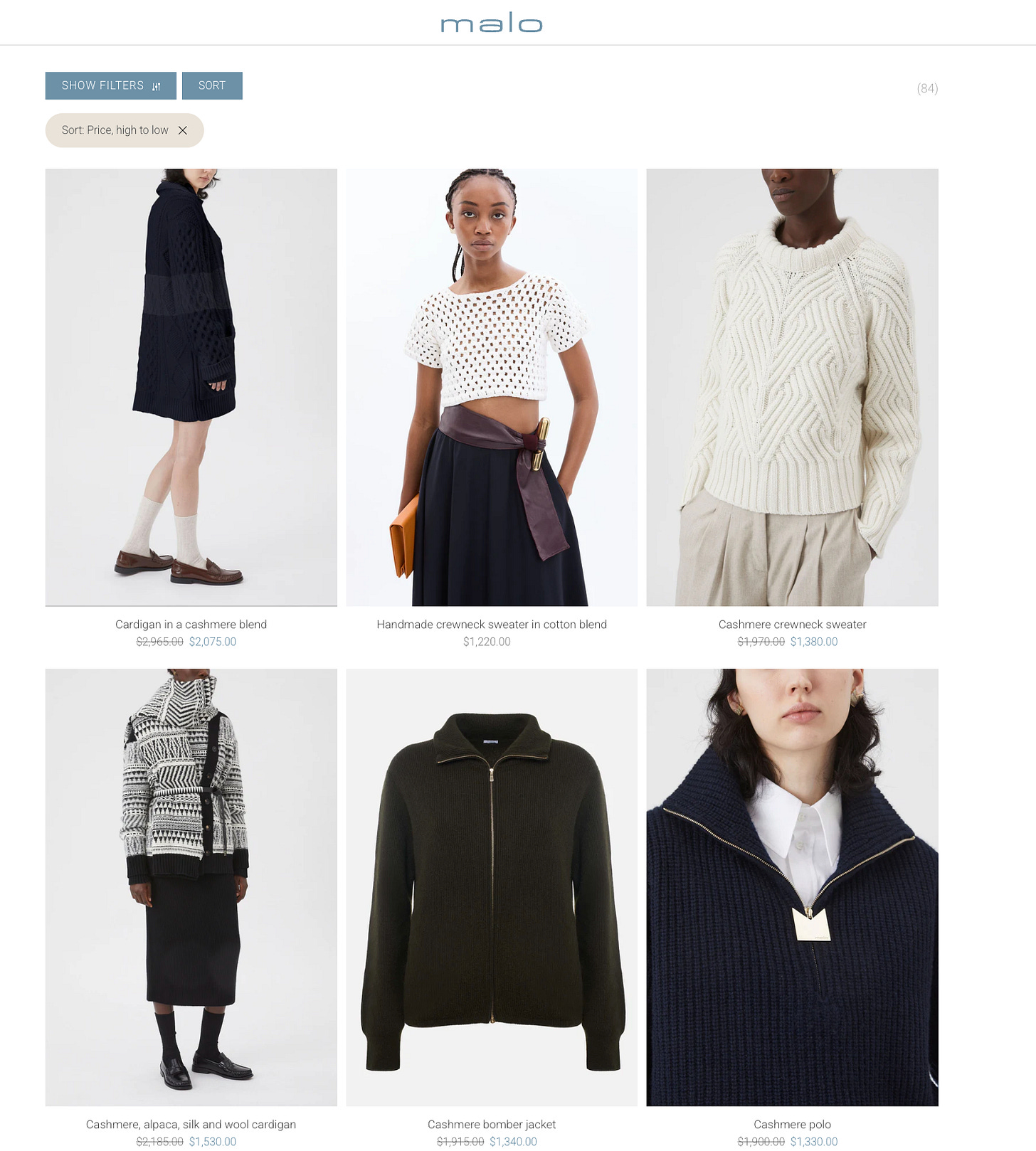

Malo

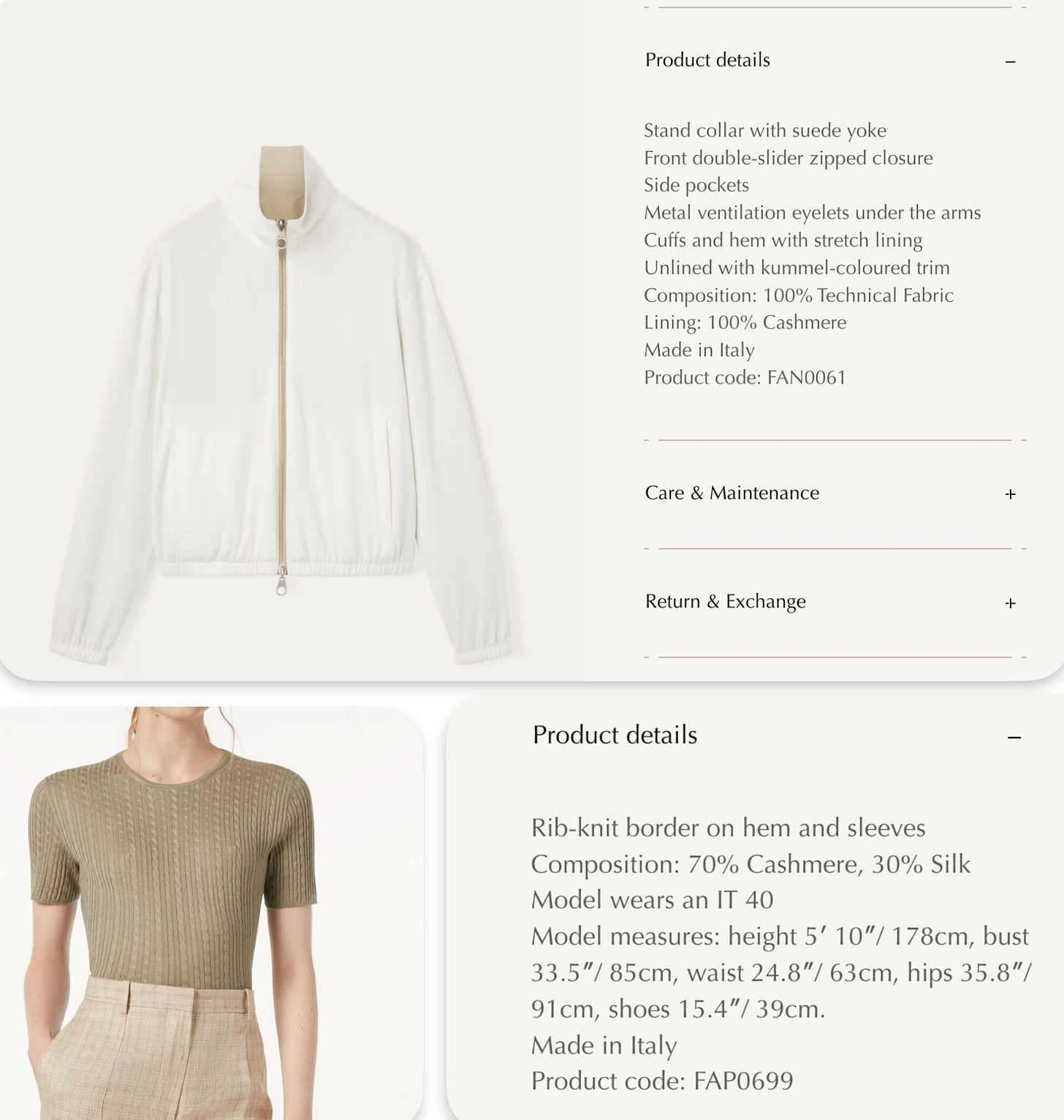

I've never seen Malo in person as there are no channels in China. Malo's recognition in China is even lower than Agnona's—I've only seen it in official website images, but they look attractive from the pictures. I initially knew Malo as a fabric supplier, but discovered their lightweight cashmere sweater series features beautiful colors—many special colors, each developed in slightly different shades.

They also have several extremely thick, heavyweight cashmere outerwear pieces, immediately suggesting this cashmere brand has substance. Despite being bought and sold multiple times, they've maintained their cashmere DNA and focus on cashmere development.

The two ribbed cashmere zip cardigans above have a flatness comparable to Brunello Cucinelli.

Their menswear cashmere style is somewhat like the British N.Peal —plain, minimalist, and clean. Like N.Peal, they frequently sponsor celebrity events and parties.

The pieces below resemble Piacenza 1733, with distinctly Italian colorful vintage style.

Malo isn't particularly famous as a fabric supplier. Although they offer various fabrics beyond cashmere, including vicuña, silk, alpaca, and merino, I couldn't find information about specific collaborations, so I'm writing about them as a clothing brand. They have multiple stores in Italy, shops in French ski resort Courchevel, Spanish resort town Marbella, and stores in Kyiv and Denmark. In Asia, they only have a presence in Taiwan.

Cashmere brands targeting old money clientele typically open stores in resort destinations. Besides Malo, Drumohr (which will be covered in part 04) and minimalist women's brand Akris follow this pattern. Mature European resort destinations are always complemented by appropriate luxury shopping streets—I wonder if I'll see China develop this way in my lifetime.

Sa Su Phi

I've recommended Sa Su Phi multiple times—you can find numerous articles by searching on my official account page. I've purchased two representative heavyweight cashmere sweaters and they remain my favorites. Sa Su Phi also has extremely low recognition in China. Founded in 2021 by two former executives from Valextra (known as the Italian Hermès), it's a new women's cashmere brand with a powerful feminine style (collections beyond knitwear aren't suitable for petite women). With forward-thinking design targeting high-end customers and substantial materials, they use Cariaggi's best yarns like Brunello Cucinelli—flat and durable. Because the brand is so new, their prices haven't yet reached BC's level.

Sa Su Phi cashmere sweaters' special characteristics were covered in 11 Minimalist Luxe Brand Elements to Elevate Your Brand Identity, and signature items in the Sa Su Phibrand series article, so I won't elaborate further here.

With this level of quality and positioning, Sa Su Phi is bound to become popular eventually. Their design quality is comparable to The Row . Beyond their standout cashmere knitwear series, they're expanding into dresses, trench coats, and suit coats, though some of these categories currently use viscose. If they can eliminate synthetic fibers and focus more on natural materials, their future development will be even better.

Sa Su Phi has the most fashionable design among the cashmere brands in this series, and is the newest brand with no real equivalent—women are truly fortunate, especially those over 170cm tall. Eddy even says he wishes Sa Su Phi had menswear. Even the name Sa Su Phi could directly translate to "Jing Lin Yu" in Chinese, rather than "Linyu Jing."

04

Among these 7 brands, only That's Alyki exclusively makes women's clothing, while Neri Firenze makes both men's and women's clothing with a slight focus on women's wear. The others primarily focus on men's clothing, with Mauro Ottaviani and Piacenza 1733 producing only menswear.

Brand history: Piacenza 1733, Drumohr 1773, Andrè Maurice 1921, Cruciani 1992, Neri Firenze 2005, Mauro Ottaviani 2014, That's Alyki 2022

Piacenza 1733 focuses primarily as a fabric manufacturer (which will be covered in section 06), offering Alxa cashmere and Vicuna. However, for fall/winter clothing, they mainly use Alpaca and llama wool blended with cashmere. Their patterns tend toward colorful vintage styles. For spring/summer, they focus on various cotton-linen and silk-cashmere blended fabrics for T-shirts and polo shirts.

Mauro Ottaviani was established by the second generation of a top-tier men's clothing manufacturer. They only produce medium to lightweight men's cashmere sweaters for fall/winter, while using various cotton-linen and mulberry silk blended fabrics for spring/summer, with a strong emphasis on seasonal fabrics. As a high-end men's clothing manufacturer, their basic cashmere sweaters have an "old money" feel.

Piacenza and Mauro Ottaviani are my favorites among these six brands. Both focus exclusively on menswear, offer affordable prices, and use various natural fabrics. Their fabric luster and dyeing quality are a level above the following four brands, with craftsmanship in the medium-high range and superior aesthetics. The drawback is that Mauro Ottaviani is too new with limited brand recognition, while Piacenza's designs are more traditionally Italian vintage, which doesn't fully align with today's minimalist trends, though the clothing itself is attractive.

For the following four brands, consider them for basic pieces, and try to choose the most expensive items in each category. As I mentioned with Sunspel , with inherently high-value brands, if you're pursuing quality, choose their premium pieces.

If I were to rank these four brands according to my personal preference, it would be: Andrè Maurice > Cruciani > Neri Firenze > Drumohr

Andrè Maurice has over 100 years of development history, substantial design experience, rich product categories, and numerous stores across Italy, including outlet stores, which is why they rank first.

Drumohr ranks last primarily because they mainly work with wool, with only a small portion of cashmere products and limited categories. Neri Firenze stands out for its hand-knitting techniques and substantial cashmere thickness, and despite being less impressive in style and fit due to its niche status, the pricing is reasonable.

Andrè Maurice is a family brand with the most diverse styles and categories among these six, including men's and women's cashmere vests, down jackets, coats, and hoodies. With many stores across Italy, many Italians purchase from them during annual sales. Their non-knitwear design is more mature than Cruciani's, making them worth buying when you find suitable pieces.

Crucianiwas established by the second generation of a lace and home textile manufacturer, mainly focusing on thin cashmere base layers, with some vests and cardigans. Their cashmere sweaters have better luster and smoothness compared to Drumohr and Neri Firenze. They also produce shirts, suits, and coats, but with less expertise in fit and design, so these categories are not recommended.

Drumohr is a Scottish brand purchased by Italians at the end of the 20th century, now in decline. They work with wool and cashmere fabrics, producing many wool sweaters and some cashmere sweaters. Their cashmere quality is average and tends to be on the thicker side.

Neri Firenze has a short history and limited connections to textile factories or textile families, making it the only one here leaning more toward being a personal designer brand. While their men's and women's cashmere quality is average, it's very thick and substantial, with hand-knitting techniques but limited categories.

Like Neri Firenze, Italy has many niche artisanal brands, especially those making various leather goods and shoes. Many have unique characteristics but lack the capital and business connections of the other brands mentioned in this article, choosing instead to persist in their small shops.

Another brand, That's Alyki though founded by the second generation of a textile family, is backed by Felice De Palma, a textile processing and fabric manufacturing company with less resources and power than Mauro Ottaviani and Cruciani. Established only in 2022, they currently only make women's clothing, with cashmere sweaters that are relatively thin with simple designs and basic fits. Their future development remains to be seen.

In writing this, I've noticed that while many say men have weak consumer power, the reality is that products on Taobao and Xiaohongshu aren't good enough. Men are more discerning; being attractive isn't enough, nor is marketing alone. Looking at these cashmere brands, both industry professionals and consumers are predominantly male. Since I started writing fashion articles, I've had a significant number of male readers, and brands focused on menswear tend to be more down-to-earth.

05

Often, the less-known mass-market Italian brands tend to produce lower quality clothing designs. They want high profit margins while selling large quantities, following a mass-market pricing strategy with poor quality and design, relying heavily on capital-backed marketing. These are typically new brands established since the 1990s, lacking the down-to-earth spirit of older generations.

Eleventy Milano has already been criticized once in that article. Their colors, fabrics, fits, and details are all unattractive, backed only by capital power. They're too eager to profit—initially promoting "Made in Italy," but later abandoning this commitment to manufacture wherever labor is cheapest, while their clothing design and fit remain subpar. Another example is Mandeli Milano menswear, which has a cheap feel—even looking at their official website gives the impression they're hastily trying to exploit consumers.

Lauren Manoogian has strong financial backing, and although based in Umbria, their designs are ugly, their website is unattractive with dull colors, they lack craftsmanship details, rarely use cashmere fabric, and the brand itself has little aesthetic value—it's just financially powerful. In mainland China, SKP promotes them, and while bloggers discuss them on Xiaohongshu, I haven't seen actual consumers purchasing.

They're essentially the women's version of Eleventy Milano.

Falconeri, established in the 90s, emphasizes value for money with basic cashmere sweaters and silk products. Initially committed to "Made in Italy," they later shifted production to lower-cost countries like Tunisia and Portugal, and began using celebrities for promotion. In 2009, they were acquired by the Calzedonia Group. In 2023, the Calzedonia Group rebranded as Oniverse to reflect its diversified businesses (covering fashion, yachts, wine, etc.), with Falconeri remaining a core brand.

Falconeri has many channels in China, including stores in Chengdu and promotions by Xiaohongshu bloggers, with some consumer purchases. They offer slightly better basic cashmere sweaters in this 05 series and might be worth considering with suitable discounts. Even though they're not "Made in Italy," the brand still maintains some quality control. However, I personally don't like them because they abandoned "Made in Italy" and couldn't stick to their original values.

Dušan, a Milan-based mass-market brand recently entering the Chinese market, is another example. They don't even promote "Made in Italy," just positioning themselves as an Italian brand, producing cashmere sweaters in Tunisia. At first glance, they appear to be an ordinary mass-market cashmere brand, and their designs are predictably mediocre.

I've noticed that these impatient cashmere brands established after the 90s are mostly founded in Milan, rather than in regions with historical textile craftsmanship like Valsesia and Umbria. The brands from sections 02-04 only open stores and showrooms in Milan after significant growth to facilitate global client access. Only major global fashion companies like Zegna and Loro Piana with substantial global influence relocate their headquarters to Milan.

06

The top-tier cashmere fabric suppliers are the same as the three brands mentioned in section 02, except Brunello Cucinelli is replaced with Cariaggi . However, BC holds the majority of Cariaggi’s shares, and the two brands collaborate very closely.

Cariaggi doesn’t have a dedicated label but does have a fabric swatch book.

Colombo’s fabric label has a red background with gold lettering. If it’s on a white background, it’s a garment label.

Apart from the three top-tier cashmere suppliers—Loro Piana, Lanificio Colombo, and Cariaggi—other well-known mid-tier cashmere and wool fabric suppliers include the historically older Piacenza 1733 and Botto Giuseppe , introduced in section 01. They were born in the era of manufacturing and naturally carry the DNA of that era, focusing more on wool with some cashmere. In China, they are also more popular among small shops and mid-tier brands that emphasize cost performance.

These five brands, except for Cariaggi (which primarily blends wool with cashmere and in which cashmere dominates), all produce pure wool fabrics to varying extents. The three top-tier brands lean more toward cashmere, while the two mid-tier ones are more common in wool and alpaca blends, catering to a broader market.

These five brands have decent popularity and traffic in China. Many mid-to-high-end Chinese womenswear brands and Taobao shops use their fabrics and often highlight this prominently. But there are three common pitfalls:

Just like with ready-to-wear, the same fabric brand can have many quality tiers—sometimes as many as jasmine tea grades from Wu Yutai. Most Chinese brands are positioned at lower tiers and are unlikely to access premium fabrics. Even Loro Piana’s fabric suppliers (ING LORO PIANA & C) offer cheaper wool fabrics. Some Taobao and Xiaohongshu shops even collect leftover stock to resell, promoting it with big names, but people only end up remembering the fabric supplier, not the actual brand.

When looking at fabric collaboration, you also have to see whether it’s the supplier’s top-tier fabric. The Botto Giuseppe scarf I previously bought was made from Botto Giuseppe’s top-grade vicuña fabric. Even though the percentage was small, the effect was superb, since the accompanying cashmere was also Dreyden’s finest, Italian-processed, and finished cashmere.

Botto Giuseppe is quite typical of many knitting factories founded in the 18th and 19th centuries. They started cashmere production in the late 19th century, doing processing work for a few British luxury brands and selling their own cashmere scarves. Luckily, Botto Giuseppe still has a fabric business. Those few British brands no longer do; much like the UK itself, they’ve declined and don’t really manufacture anymore. After the first Industrial Revolution, they missed the rest. But it’s a great place for writers and artists to retire by the seaside.

Piacenza 1733’s best lines include Alashan cashmere and vicuña, but its Chinese partners mostly use the cheaper llama and wool lines. Piacenza also partners with brands; for example, Chinese export brand Chicjoc collaborates with them, but definitely not on their core offerings. Core pieces are better bought directly.

For Loro Piana, you need to look for core fabric series like Storm System. I’ve seen brands like Akris and Paul & Shark use Loro Piana’s Storm System cashmere for their most expensive coats and trench coats—these are indeed pricey. The fabrics below are more common and not part of their core series, mostly used by suiting brands.

Another situation is when a brand promotes these fabric suppliers endlessly, giving the impression that all garments are made from their fabrics, when in fact only one or two pieces actually are. Even China’s best brand, ICICLE, is like this—and it doesn’t even use Loro Piana’s core fabrics.

The third situation is when a garment includes only 10% of the named fabric. Whether that’s good depends: if it’s 10% vicuña, not bad; if it’s just generic cashmere-wool, then it’s really not worth mentioning.

These five brands are the most globally recognized and scaled cashmere fabric suppliers that I know of. Malo and Mauro Ottaviani, while also having fabric-related content, seem more like OEMs. Even though they invent some new fabrics and textiles, they likely have more local partnerships in Italy. They aren’t very well-known, and there’s limited online information. I haven’t seen specific brand collaborations, but their official websites do emphasize fabric introductions and series.

In China, even the fabric labels of these well-known suppliers can be faked. Some fashion brands buy counterfeit fabric labels. So I’d recommend sticking to physical stores.

Epilogue

After all this, I’ve realized that Chinese brands care mostly about whether a piece is “Made in Italy” or uses “imported fabrics,” not the design, cut, or exact fabric grade. The name is what sells.

Italian brands, on the other hand, wrestle with whether to preserve their origins, uphold niche craftsmanship, whether to sell to large fashion capital groups, and whether to move production to lower-cost areas. Many second-generation factories are even thinking about launching their own brands.

Chinese consumers want Italian craftsmanship and brand premium; Italians want Chinese raw materials and vast markets. The US wants to be the next France—strong in ready-to-wear and innovative design. Emerging minimalist brands are gaining traction there. The three most expensive, avant-garde, and best-fabric minimalist brands of the new generation are all based in New York.

WeChat: pamperherself