Textile : An Introduction to World Ethnic Dress and Blankets — the Shifting Worldviews Behind Rich Colors, Textures, Patterns

Exploring Global Ethnic Dress, Blankets, and Evolving Aesthetics

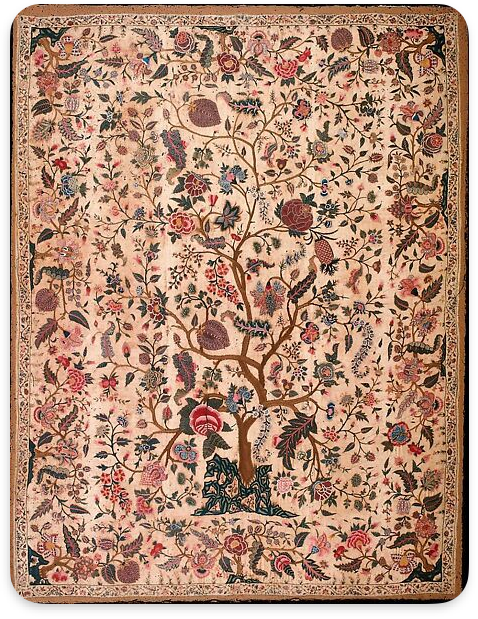

Folk costumes and blankets from around the world are vibrant and colorful, woven with geometric patterns of natural elements and deities. Zigzag patterns symbolize lightning, rivers, and mountains; diamond patterns represent eyes; circular patterns signify the sun and cosmos. Plant motifs include flowers (roses, tulips, pomegranates), leaves, vines, and trees (the Tree of Life), often symbolizing life, prosperity, paradise, or harvest. Animal patterns feature birds (peace, freedom, soul), deer (longevity, wealth), lions (strength, royalty), and fish (abundance, good fortune).

The following content is based on Beverly Gordon's "Textiles: The Whole Story: Uses, Meanings, Significance," focusing on the colors and patterns of folk costumes and quilts. It systematically introduces the dyeing and decorative materials, weaving techniques, and the world stories embedded within them. This article is quite lengthy, approaching six thousand words, equivalent to the combined content of Textile:Thread and Textile:Network. Together, these three pieces provide a preliminary understanding and introductory exploration of world traditional costume culture.

Color

The rich colors of folk costumes and regional blankets reflect humanity's innate yearning for brilliant, vibrant, and bright hues. In regions worldwide where natural environments are dry, desolate, and lacking in color, people enrich their visual experience through colorful, life-filled textiles.

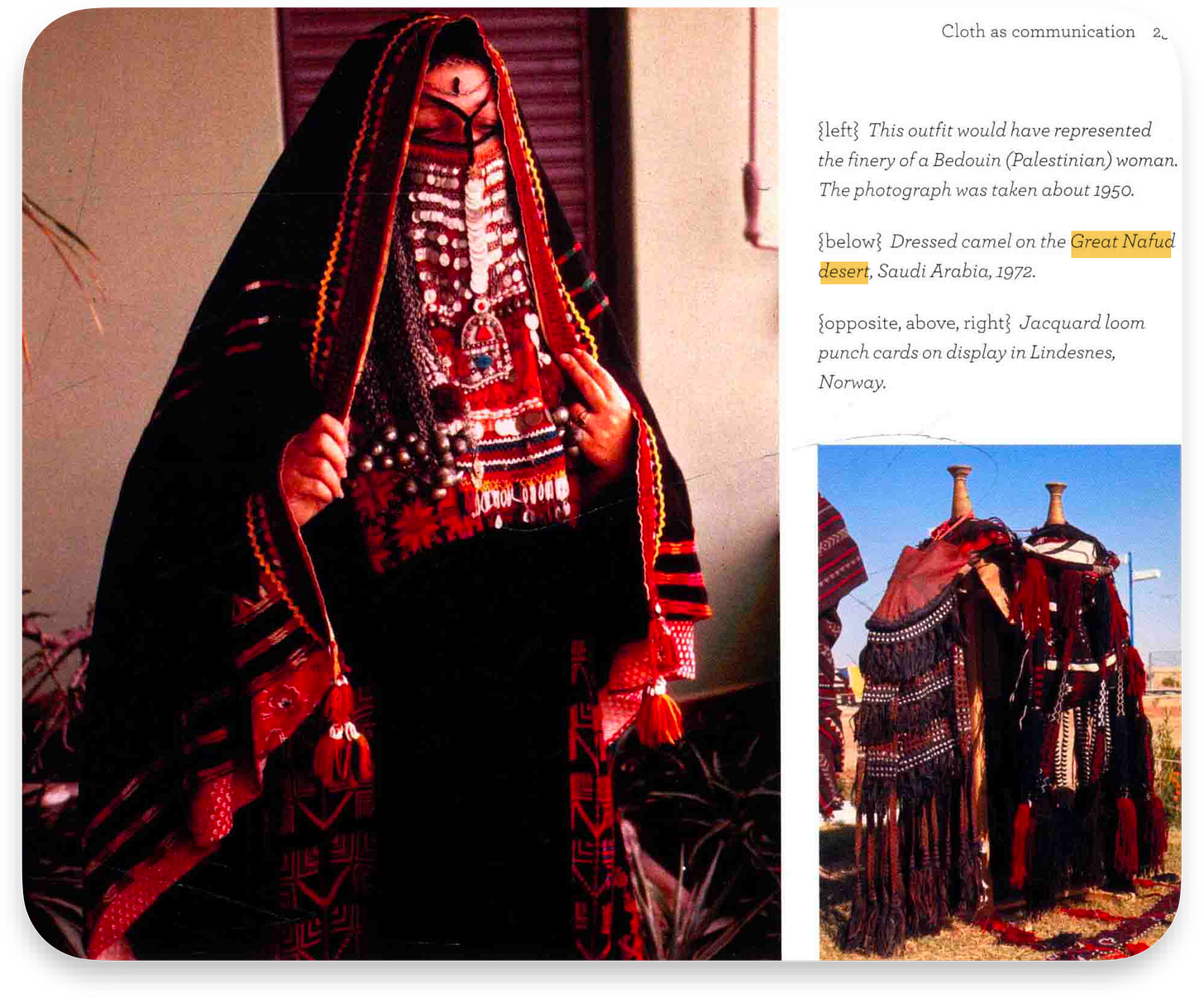

For example, Rabari and Kutch women in northwestern India commonly wear bright orange and deep red, embedding small mirrors in their garments that sparkle and dance with movement under sunlight. Moroccans in the Sahara Desert and Mongolians in the Gobi also create exceptionally bright fabrics. On the Central Asian steppes, where trees are scarce and winters are completely snow-covered, people decorate every inch of their tent surfaces with vivid, intense fabrics, even adorning their pack animals with colorful patterns and decorative tassels.

Similar phenomena occur in Sweden and other Nordic regions—long winters and endless nights lead people to decorate their spaces with bright fabrics, even in the most modest households. Every table is covered with handcrafted textiles, and every ordinary towel is overlaid with an exquisite "display towel" that is removed only when needed.

New immigrants to North America lived in dark houses lacking natural light, making the "summer garden" colors of Indian chintz cotton particularly popular. When a ship loaded with such fabrics arrived at Boston Harbor, housewives competed so fiercely that it nearly caused a riot (even though England prohibited Indian printed cotton, it could still circulate in the colonies). I will write a dedicated piece about chintz cotton later.

Dye

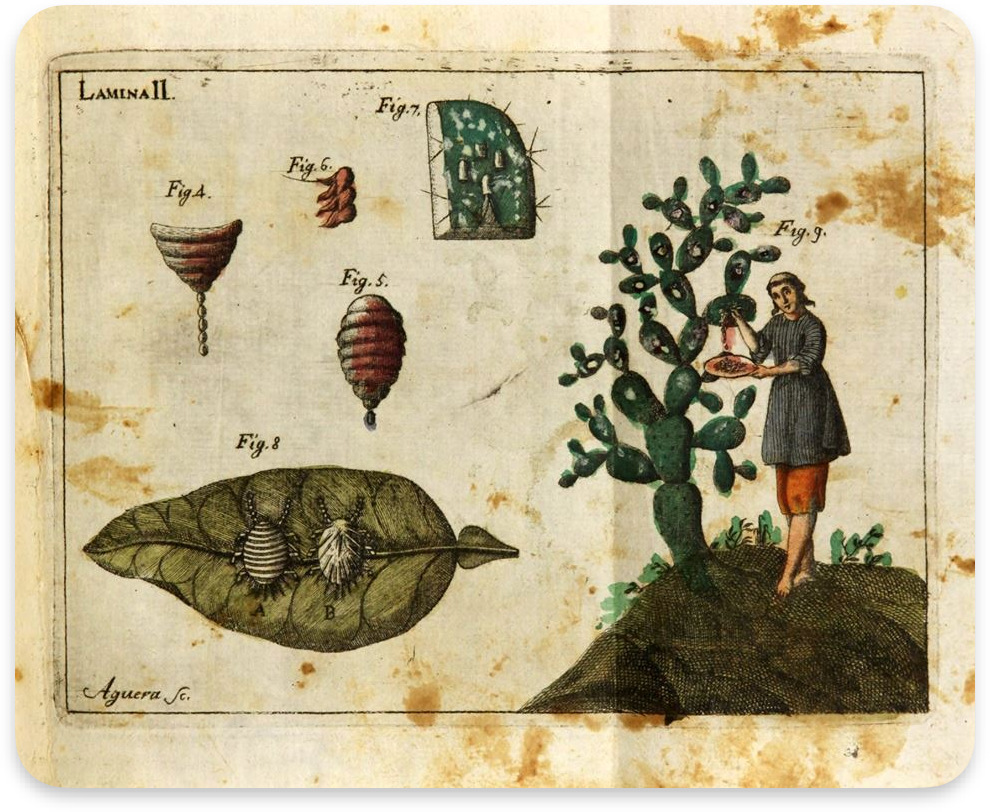

In the mid-19th century, German chemists invented synthetic dyes, which expanded the range of color choices while making dyeing processes more stable and affordable. Before this, natural dyes such as indigo, madder, and cochineal red were most commonly used.

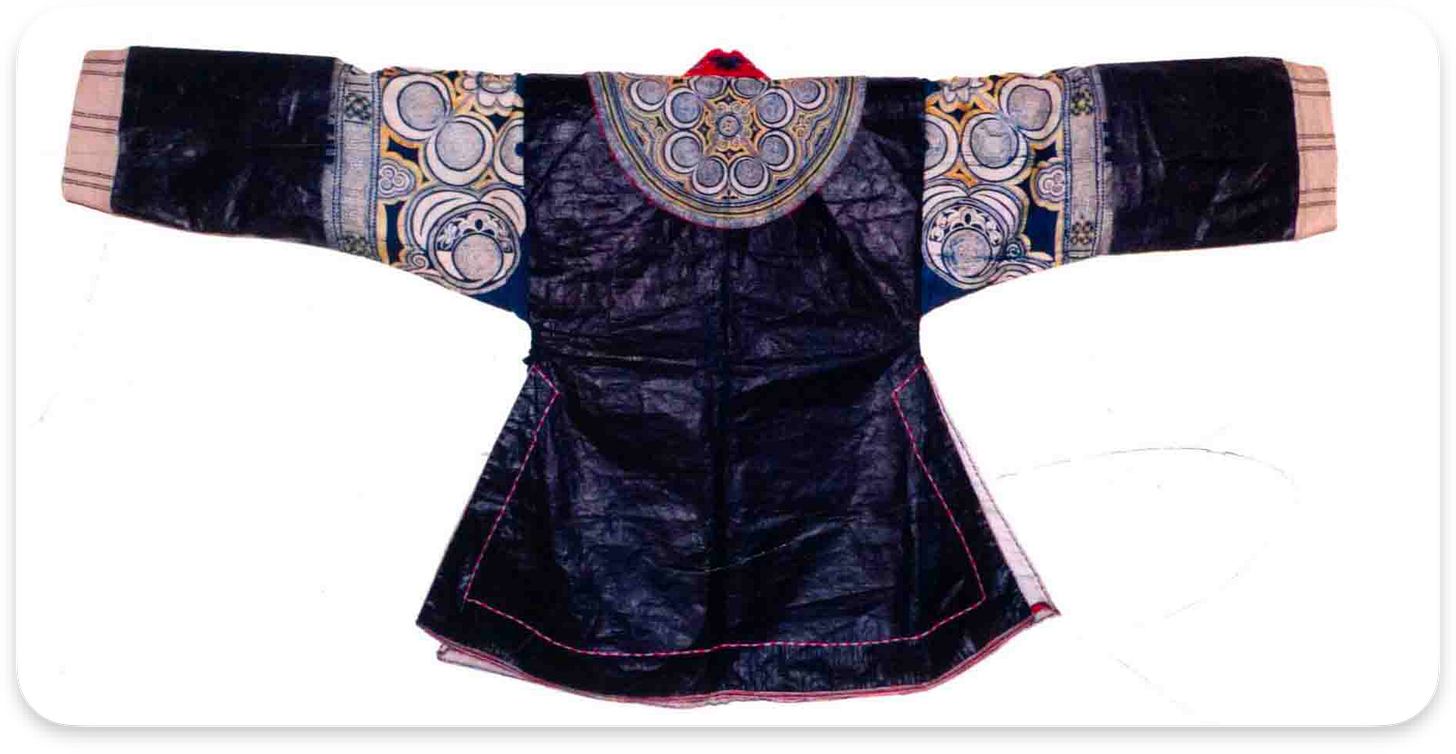

The image below shows Miao ethnic clothing, where silk fabric is dyed black through multiple indigo wax-dyeing processes and rubbed to reveal irregular textures.

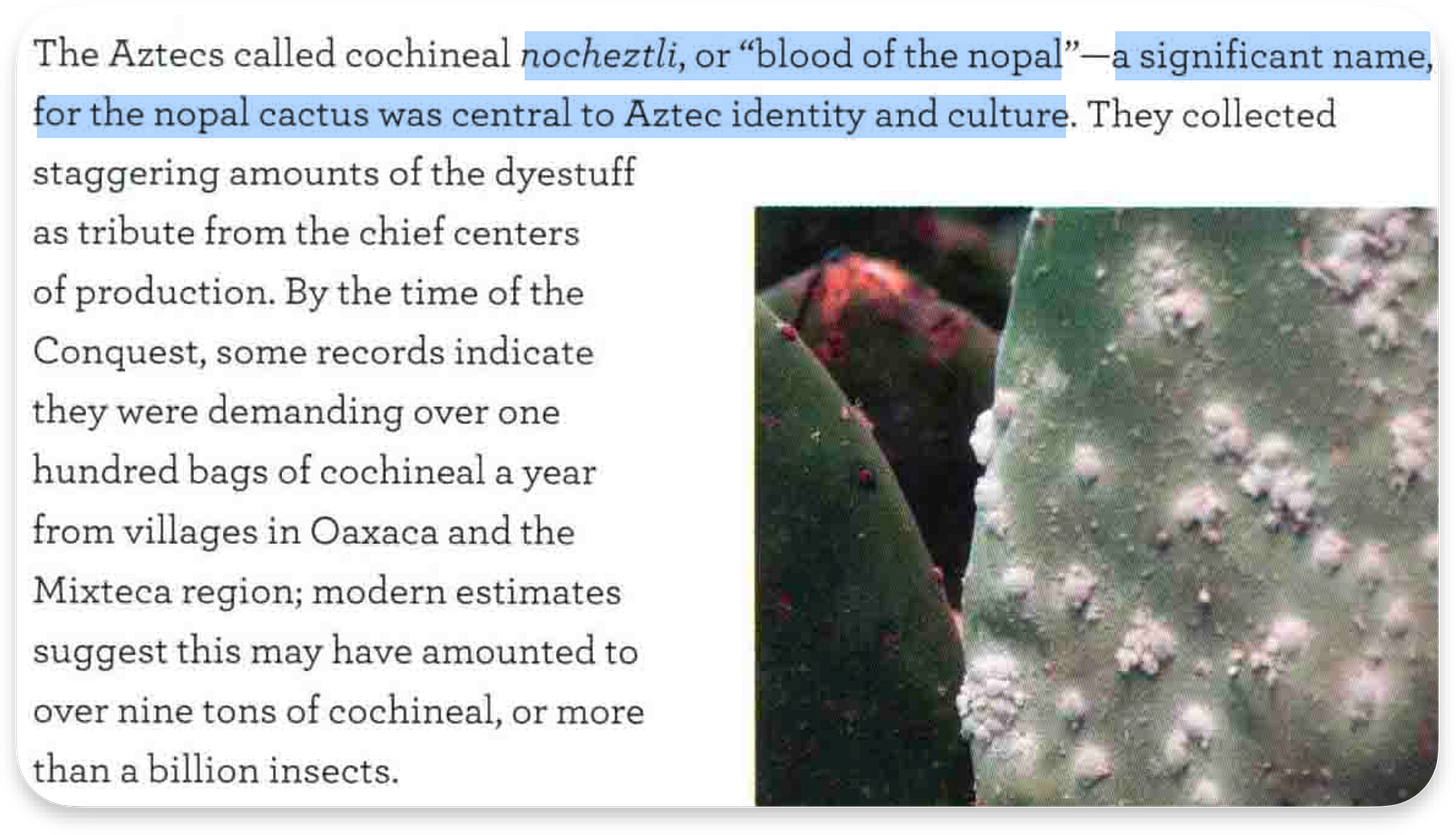

The Aztecs of Central and South America cultivated and produced nocheztli cochineal insects. The Aztec word nocheztli is composed of nochtli (cactus) + eztli (blood), reflecting the Aztecs' sacred perception of this dye.

When South Americans first encountered industrial society and industrial chemical red dyes, they would even unravel red threads from existing textiles to sew their own garments.

Due to its brilliance and colorfastness, cochineal dye was once ranked alongside gold and silver as an important source of wealth in the Aztec tribute system. During the Age of Exploration, it created a sensation in European markets, with commercial value second only to silver, becoming the globally recognized premium natural red dye.

Cochineal red was controlled by Spain in the New World, and its source was kept secret for a long time. It is said that one pound of dye required approximately seventy thousand insects. Due to its extremely high value, ships carrying cochineal were frequently attacked by pirates.

Some lipsticks today still use cochineal as a red pigment. Minerals were also used as dyes in the past, with asbestos being the most well-known, but this mineral has been proven toxic and is now rarely used. Traditional costume dyeing today typically refers to plant dyeing rather than mineral dyeing, as minerals are generally toxic.

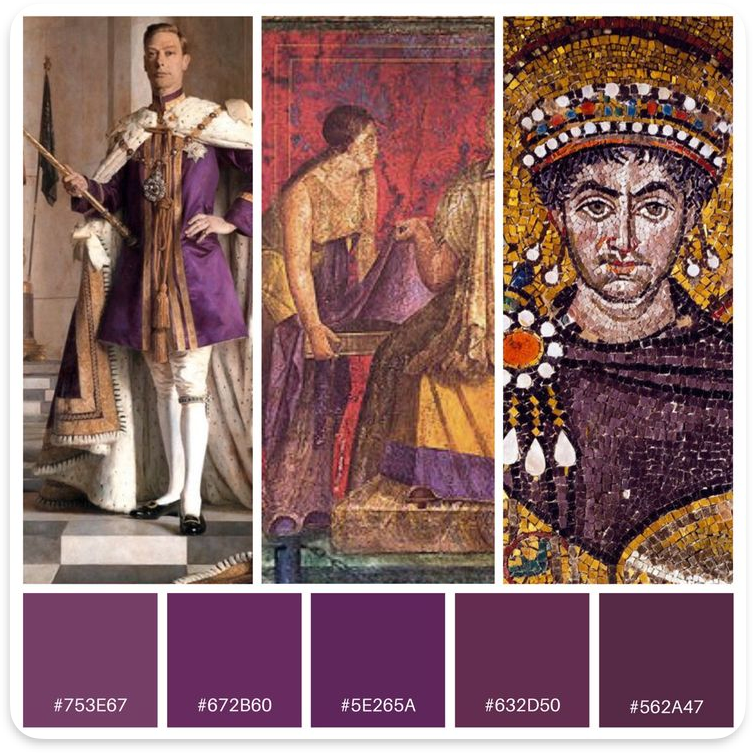

The most noble Tyrian purple, though produced in small quantities, cannot be overlooked in the history of natural pigments.

In the past, this expensive purple was extracted from two types of murex shells: Murex brandaris (purple-red dye) and Hexaplex trunculus (slightly blue-purple, also called royal blue dye).

Ornamentation

Beyond dyes, many traditional costumes rely on various decorations, such as the fringed garments made with dyed porcupine quills and various bead-decorated accessories of Northeastern American Indians mentioned in the previous two articles Textile:Thread, and the Indian turkey feather blankets and New Guinea feather net bags bilum mentioned in Textile:Network

Egyptian shawls use fine tulle or cotton gauze as a base fabric, adorned with small pieces of silver or metal Assyut silverwork. The patterns are geometric shapes, florals, and decorative motifs, sometimes with Oriental or Art Deco style, popular during the 1920s Egyptian tourism boom.

Since silver can be inlaid in garments, gold is even more prevalent. Gold is made into small bead-like shapes or formed into golden threads to create patterns, used in Chinese dragon robes and Western papal and imperial coronation embroidery.

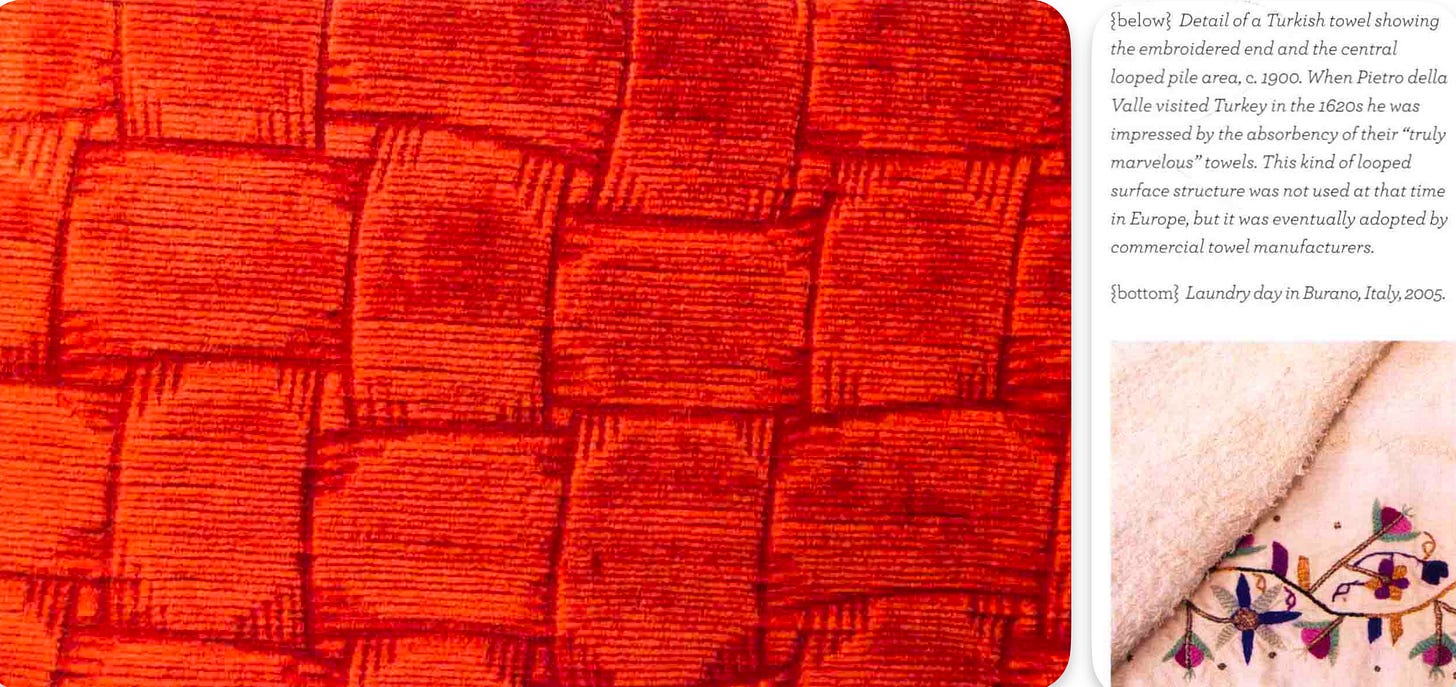

Europe made greater use of velvet, which employs a tabby pattern with two stacked textile techniques. The looped pile texture we take for granted in towels originally came from Turkish towels, as this texture provides better water absorption.

Silk, velvet garments, and carpets adorned with gold, silver, and jewels were all symbols of royal power. In 1599, at the Persian court, Anthony Sherley reported that the "roads" of Isfahan were covered with velvet, satin, and gold cloth for two miles (about 3 kilometers), over which Safavid ruler Abbas the Great rode in procession. The palace was also laid with exquisite carpets, sometimes inlaid with thousands of gems and pearls, so magnificent that European envoys complained about the difficulty of walking on the ground.

Ottoman, Byzantine, Persian, and Mughal rulers all had diplomatic customs of gifting carpets. Like Westerners conferring medals, they bestowed beautiful robes upon government and military members, visiting dignitaries, and envoys. They also used robes to reward specific activities, such as intense wrestling matches, clever poetry, or even family celebrations.

Rulers sometimes exchanged khil'at for diplomatic purposes. A robe (usually including turban, belt, trousers, and shoes) would be publicly bestowed in public settings (such as courts or battlefields). This tradition was most prevalent in the Near East, South Asia, and Central Asia from the 9th-10th centuries and continued until the 19th century in some regions.

Ancient China and pre-Columbian Andean cultures gave fabric as gifts.

Besides gold, silver, and jewels, colored insects were also used for decoration. Thai Beetle-wing Embroidery sews beetle wing covers (elytra) with metallic green iridescent effects onto shawls, formal wear, and jewelry, mainly from Buprestidae (metallic long-necked beetles), such as Thailand's Sternocera aequisignata and Japan's Chrysochroa fulgidissima, commonly called Jewel beetles.

Pattern

The previous section discussed colors and jewelry decorations; this section focuses on patterns. We'll organize this by the techniques used to create patterns, their mythological symbolism, and the stories they tell.

Technique

The word "Ikat" originates from Malay-Indonesian, meaning "to bind" or "to tie," reflecting the core of its production process: before weaving, yarns are bound, dyed, and then woven into fabric in a specific sequence to form patterns. These patterns are not printed by modern machines, traditional batik, or mud-resist dyeing after the fabric is woven.

Indonesian ikat follows the same principle as Japanese kasuri, Indian patola, and Guatemalan jaspe.

Ikat includes Kente cloth worn by Ghanaian royalty in West Africa.

Traditional kente cloth is made from expensive silk, and its production is exceptionally time-consuming and labor-intensive. Weavers don't create wide fabric pieces; instead, they weave independent strips about 6 inches (15.5 cm) wide. Each strip contains complex jacquard patterns (formed by manually lifting individual threads one by one). These strips are then hand-sewn together to form a complete cloth.

The essence of ikat lies in dyeing technique, where yarns are dyed before weaving. By binding different parts of the yarn to prevent dye penetration, artisans create gradated colors and complex patterns. After dyeing, the yarns are unbound and used as the foundation for weaving.

Observing the image above, both the warp and weft threads of Kente cloth are dyed. The simplest ikat involves dyeing either only the weft threads to create patterns, or only the warp threads. Ghanaian kente and Indian patola use both, making them more complex and time-consuming.

Patola represents the pinnacle of Indian dyeing and weaving, no wonder the Indonesian Toraja people hold patola in such high regard. Villagers from Tenganan Pegringsingan in eastern Bali also weave their own double-ikat cloth called geringsing, with patterns similar to patola.

The diamond geometric patterns somewhat resemble eyes.

In Bali, patola represents secular power like among the Toraja, but uniquely, the patola variant geringsing is also believed to have healing properties for mental illness. People cut it into small pieces and burn them, having patients inhale the pungent smoke. Therefore, some precious textiles show small gaps.

Traditional Indian sari patterns are all patola (though some are now ordinary machine-printed). The sari is not just clothing but also a daily tool. The pallu (the end draped over the shoulder) can wipe sweat, clean tables, provide shade, cover the face (for smog protection), serve as insulation, and even bind keys or change.

Mexican rebozo and Guatemalan tzute can serve as shawls, but also carry babies, transport firewood, or hold food.

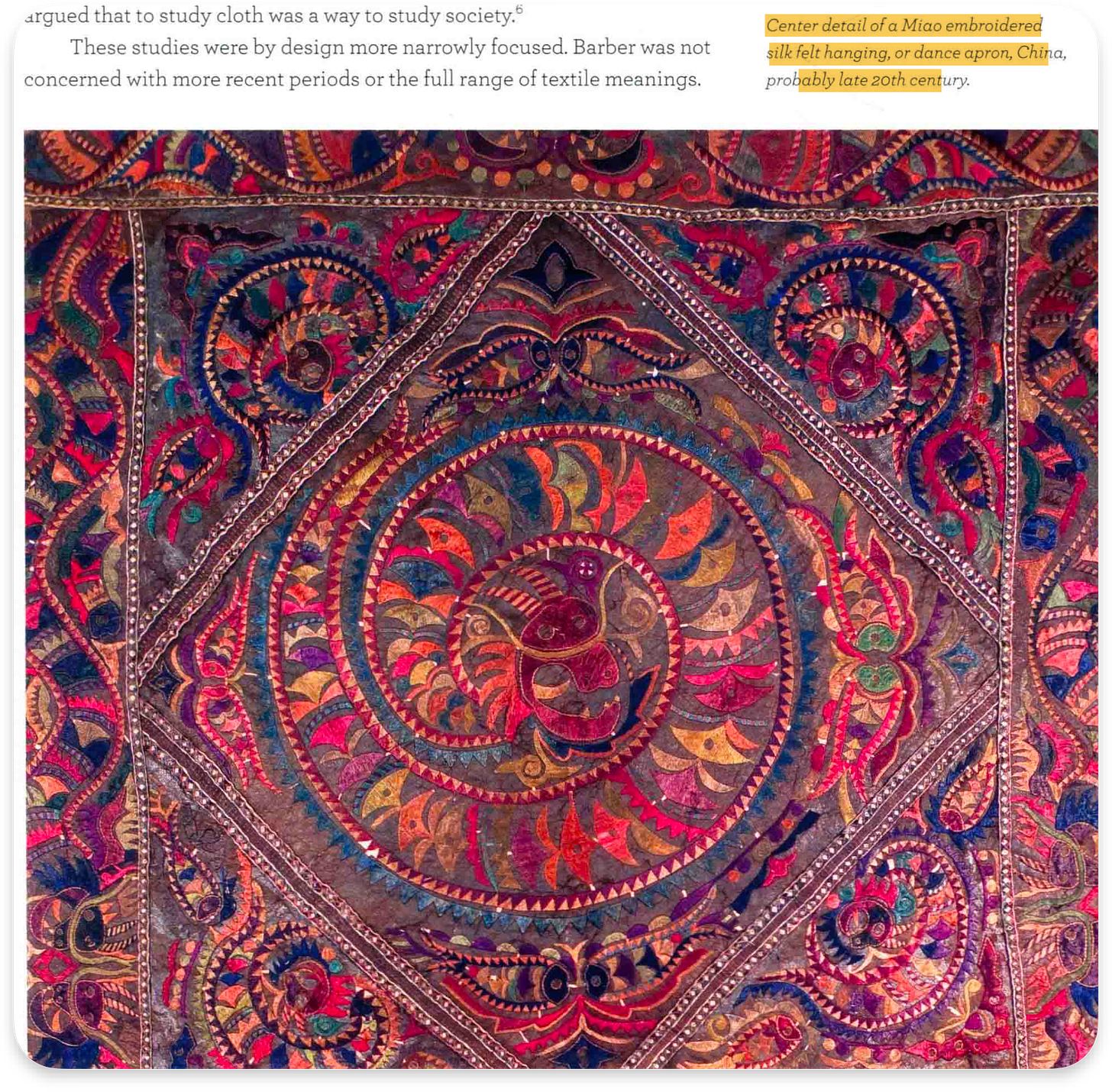

Besides weaving, there's also common felt made through compression. The Central Asian and Mongolian yurts introduced in Textile:Network use compressed felt. Felt patterns can be like the apron patterns of Miao ethnic clothing below, where silkworms are first forced to create flat mulberry silk bases (equivalent to silk felt), then patterns are painted on.

There's also a method like these women below, where patterns are first laid out, then felt is made using different colored wool threads.

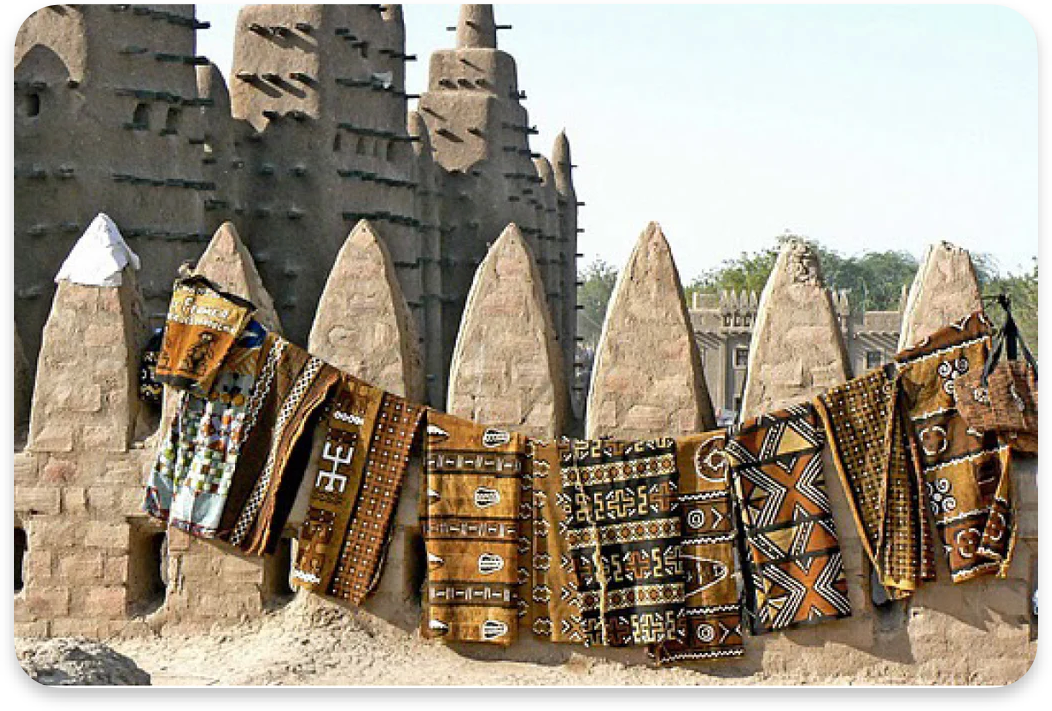

Besides the ikat tie-dyeing mentioned earlier, Miao batik (using wax as a resist agent to prevent dyeing in specific areas), and African mud cloth uses fermented mud as dye.

The traditional production process of Mali's African mud cloth Bogolanfini:

① Using local cotton, hand-spin yarn and weave cloth strips on narrow looms (usually by male craftsmen). These strips are then joined and sewn together to form a complete fabric, creating the foundation for mud cloth.

② Dye the base color with plant liquids. Soak the fabric in tea-colored or yellow plant dye made from tree bark (such as n'gallama bark) or plant leaves. The dye contains tannins, making subsequent mud-dyed patterns more permanent. After repeated dyeing and drying, the fabric shows yellow or ochre tones.

③ Use black iron-rich mud collected from rivers or marshlands. This mud needs to ferment for weeks to months, becoming thicker and richer in iron oxide. Craftsmen (mostly women) use brushes or bamboo sticks dipped in mud to draw patterns on the fabric. These patterns are abstract expressions of family, tribal, mythological, or natural symbols.

④ Iron ions in the mud react with the plant-dyed base, turning mud-dyed areas dark brown to black, while undyed areas retain their original color.

⑤ After drying, the fabric is washed to remove surface mud, but the patterns have been "printed" onto the cloth. Some patterns may require repeated mud application, washing, and correction to achieve sufficient color depth and pattern clarity.

⑥ The fabric is dried, folded, and trimmed. The finished mud cloth is sturdy, rustic, with durable patterns.

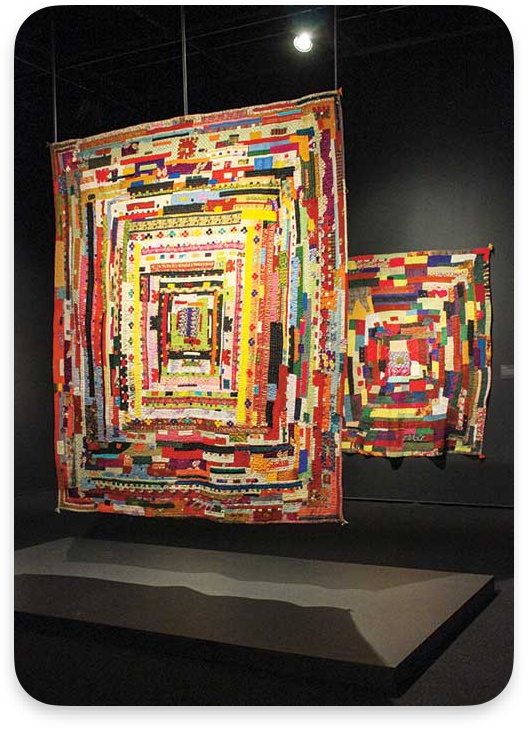

Another common method for creating quilt patterns is quilting, like kente strip piecing, joining scattered fabric pieces together, typically joining old clothes into blankets. Africa has the most patchwork.

African-American Gee's Bend quilts from migrants to America symbolize resilience and creativity amid poverty, now highly valued by the international art world. Gee's Bend is a remote African-American community in Alabama, where quilting art has been passed down from grandmother to grandmother.

American indigenous quilting comes from Hawaiian quilts, handmade baby quilts passed down as family treasures, featuring centrally symmetrical patterns depicting pirate groups.

America also has passage quilts, borrowing techniques and spirit from African-American (like Gee's Bend community) and white farming patchwork traditions, emphasizing "sewing memories from old things." It's closely related to "death, bereavement, and healing" memory quilts, bereavement quilts, or memorial quilts.

Passage Quilts from late 20th to early 21st century are widely seen in communities emphasizing death and mourning in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, and other places.

Patchwork quilts made from deceased relatives' clothing (such as shirts, bathrobes, scarves, dresses) serve as media for mourning, comfort, and memory preservation. Distribution scenes: commonly appear in funeral preparations, healing workshops, sewing activities recommended by funeral consultants, and as family memorial objects made by relatives themselves.

A century earlier than passage quilts (late 19th century), the British and American middle class favored luxurious and complex Victorian "Crazy Quilts," pieced together from various dress fabrics, ribbons, brooch materials, and fabric scraps, serving as family memorial "scrapbooks" preserving memories of family activities, travels, etc., also bearing highly personal emotions and object histories.

Comparing with the passage quilt above, crazy quilts are obviously more luxurious and textured in materials.

Indian Siddi patchwork also exists because the Siddi people are of African descent, having settled in Karnataka, Gujarat, and Maharashtra states of India over the past five centuries. Siddi communities in these regions don't share common African historical backgrounds or single origins; they came to India through different routes—some as soldiers, merchants' attendants, or slaves on trading ships.

Each community typically has different names based on their perceived place of origin. In northern Karnataka state of India, the Siddi presence can be traced back to about the 16th century. Most scholars and elderly community members believe they came to India aboard Portuguese trading ships. These vessels sailed along Indian Ocean routes, connecting Africa's eastern coast and Arabian regions with India's western coast. The Siddi people in Karnataka have largely integrated with local culture, including religion, clothing, diet, and language. The adoption of quilting is one form of this cultural fusion, using old saris for decorative patchwork patterns.

Siddi patchwork creation usually begins with a vague design concept, but this concept need not be strictly followed; during the sewing process, the creation naturally takes shape. Each quilter's intuitive feeling for color and the shapes and patterns naturally occurring in their surrounding environment influence the design and patterns on the final product.

A patchwork quilt is made by joining multiple layers of old, used fabrics together, covering them over a base fabric usually composed of one to two saris sewn together lengthwise. Each time a new fabric layer is added, it's sewn along the edge where new and old fabrics meet using the most basic running stitch.

Fabrics are traditionally taken from old clothing within the maker's own household, so each patchwork quilt uses unique colors, patterns, and textures. Making such a quilt often takes weeks; they are not only sturdy, durable, and easy to repair, but are often passed down through generations.

Korea uses leftover fabric scraps from making hanbok to create "wrapping cloths" (pojagi), used to wrap important documents or memorabilia, symbolizing respect for family memories. But unlike the large family patchwork quilts above, these aren't passed down through generations.

Illustrations

The most obvious representation of worldview in textile patterns is the Chinese dragon robe. Its composition and layout correspond to the directions, nine palaces, and twelve divisions in Chinese cosmology. The patterns are repetitive and consistent, embodying an "orderly" worldview: dragons, as the most powerful mythological creatures, guard the center and main directions. They are placed in scenes containing heaven and earth elements—water below, mountain-shaped earth blocks in the center, and rolling cloud bands above... Each pattern carries auspicious meaning.

However, the dragon robe can only truly exert its symbolic power when worn by the emperor: with the emperor's feet on the ground and head topped with auspicious clouds, it signifies his ability to unite heaven and earth and maintain cosmic order.

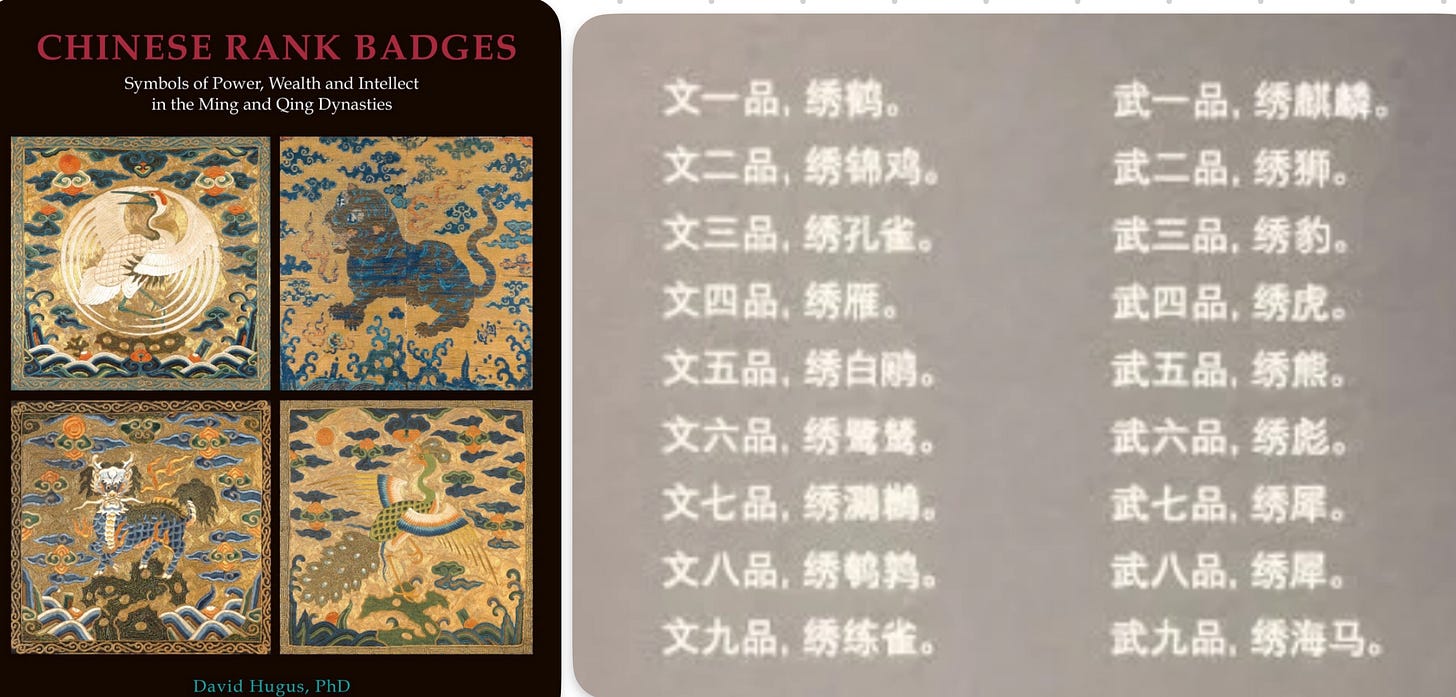

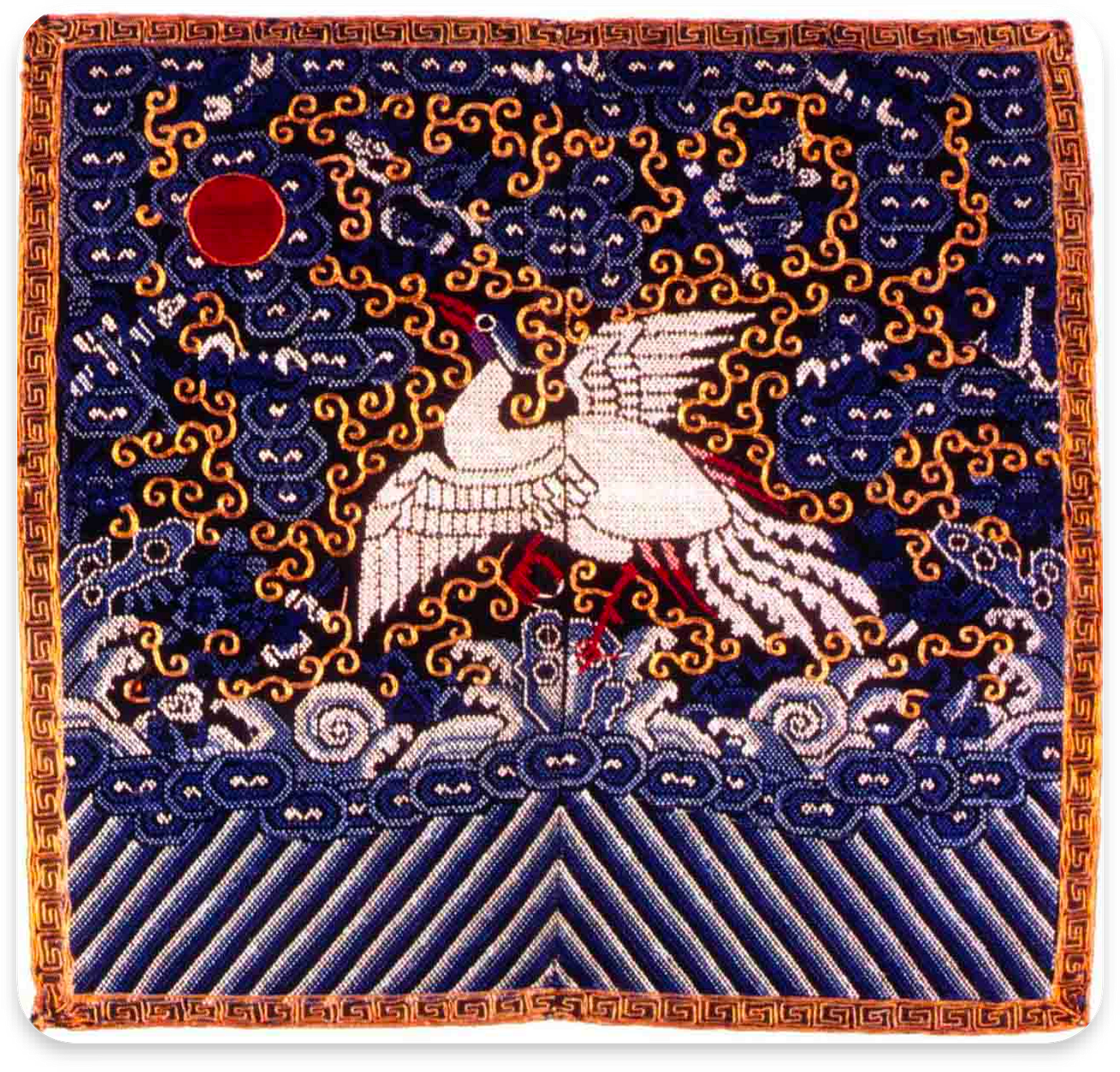

The rank badges of civil and military officials during the Ming and Qing dynasties also featured animal symbolism—civil officials wore bird patterns while military officials wore fierce beast patterns. Like Miao apron patterns, they were made of silk using exquisite embroidery or weaving techniques, containing a standardized set of symbols representing the universe and order.

The white bird below represents a fifth-rank civil official.

The traditional women's blouse huipil from the Santo Tomás Chichicastenango community in Guatemala also symbolizes the universe. When laid out, this garment forms a cross shape pointing to the four directions, similar to the dragon robe's symbolism. The endpoints of the cross are usually decorated with floral motifs. Although the huipil is worn by ordinary women, when her head emerges from the neckline, it completes the symbolic message—like the rising sun. Its spatial structure and light-dark arrangement again reflect proper correspondence.

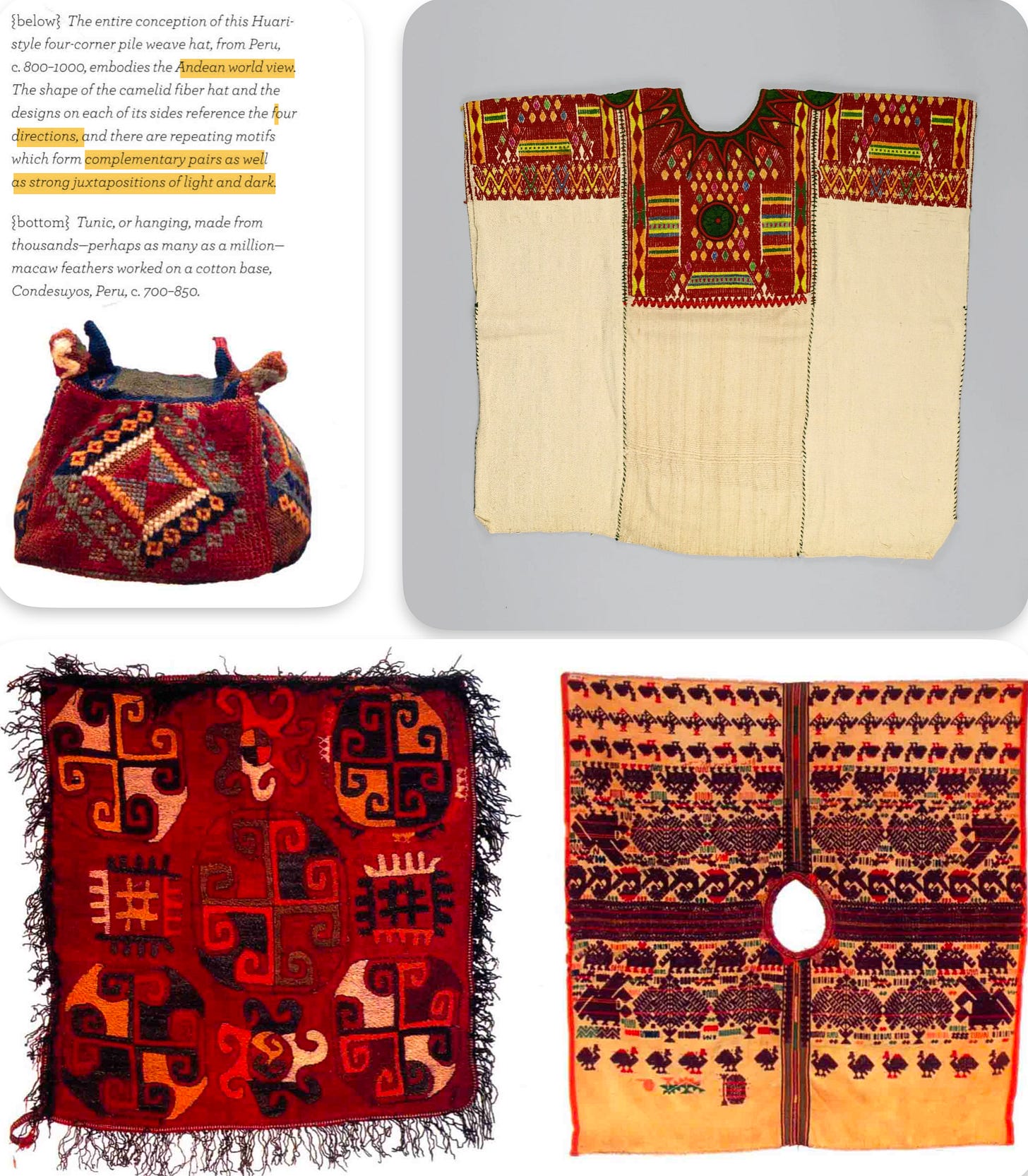

Unexpectedly, pre-Columbian South America also favored symmetrical complementarity and four directions.

Triangular patterns are generally considered to have protective functions against evil. Eastern European women embroider small zigzag lines called "wolf teeth" on shawl edges to dispel negative energy (such as the "evil eye"). In Southeast Asia's "Golden Triangle" region, mountain tribes also incorporate zigzag or small triangular patterns in fabrics for the same reason. In North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia, three-dimensional triangular amulets are sewn onto clothing, baby cradles, and even horse harnesses. The triangle itself is viewed as a powerful symbol.

Shamans use different types of textiles, dance, and drumming to alter states of consciousness.

Shamans are people who can communicate between everyday reality and the spirit world, generally entering "trance states" through ecstasy, trance, drumming, dancing, and other methods to communicate with spirits, ancestors, or natural spirits. They believe everything has a spirit—mountains, rivers, trees, animals, wind, fire, thunder, and lightning all have souls. This exists widely in indigenous cultures of northern Asia, Northeast Asia, North America, South America, Southeast Asia, Africa, and other regions.

Their clothing often has sewn attachments. Among the Inuit, shamanic clothing traditionally uses finely pieced leather, even containing actual parts of guardian animals—such as bird wings, claws, or entire weasel pelts.

In Mongolia, shamanic clothing often incorporates metal items; in Manchuria, shamanic attire typically includes iron antlers, cloth strips, mirrors, bells, and shell-decorated collars.

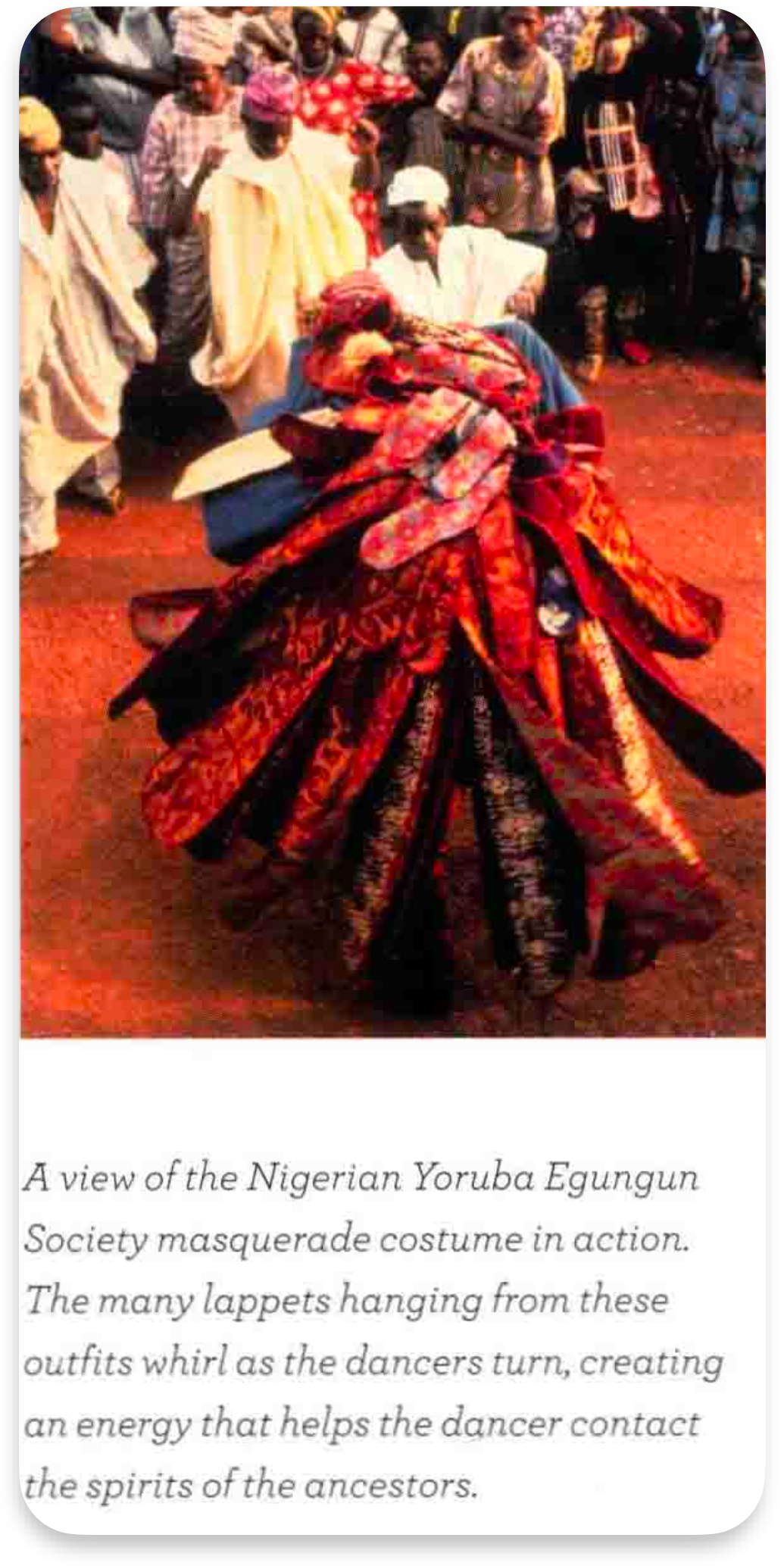

In the masked dances of Nigeria's Yoruba Egungun Society, flowing fabric curtains enhance the ritual power of connecting with ancestral spirits, with the fabric whirlpools created during spinning helping dancers enter the spirit world.

Prayer flags in the Himalayan region send prayers and blessings with the wind, typically consisting of strings of colored rectangular cloth pieces hung horizontally. They are often printed with scriptures—such as Sanskrit mantras affecting invisible energy (most commonly the six-syllable mantra "Om Mani Padme Hum") or simplified Buddhist scripture content. These flags are hung at mountain passes, temple stupas, bridges, rooftops, and around residences, left to weather and disperse. People believe prayers thus remain eternal in the universe. Resonating with life's natural cycles, Tibetans continuously hang new flags beside old ones.

Starting here, I'll introduce some more modern industrial patterns that can directly depict text, proverbs, or tell stories.

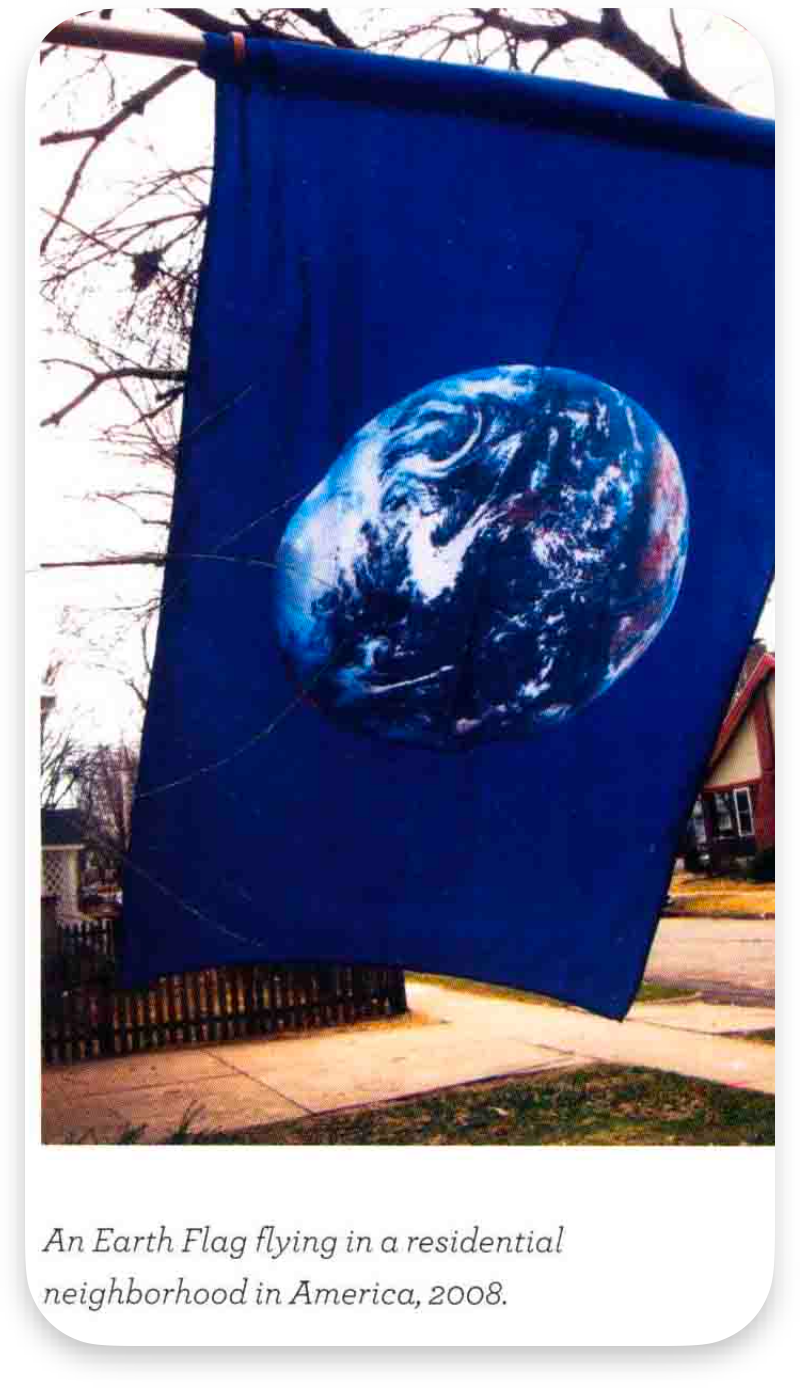

When NASA's 1969 moon landing images of Earth from space were broadcast on television, humanity could examine its own planet from a macro perspective. Idealist John McConnell printed this image on flags and put them into production. Soon, people across America launched initiatives hoping every elementary school classroom would have an Earth flag. Although this goal was never achieved, Earth flags are now commonly used to promote ecological awareness and ethnic diversity. Many classes compete to obtain an Earth flag like Boy Scouts competing for badges.

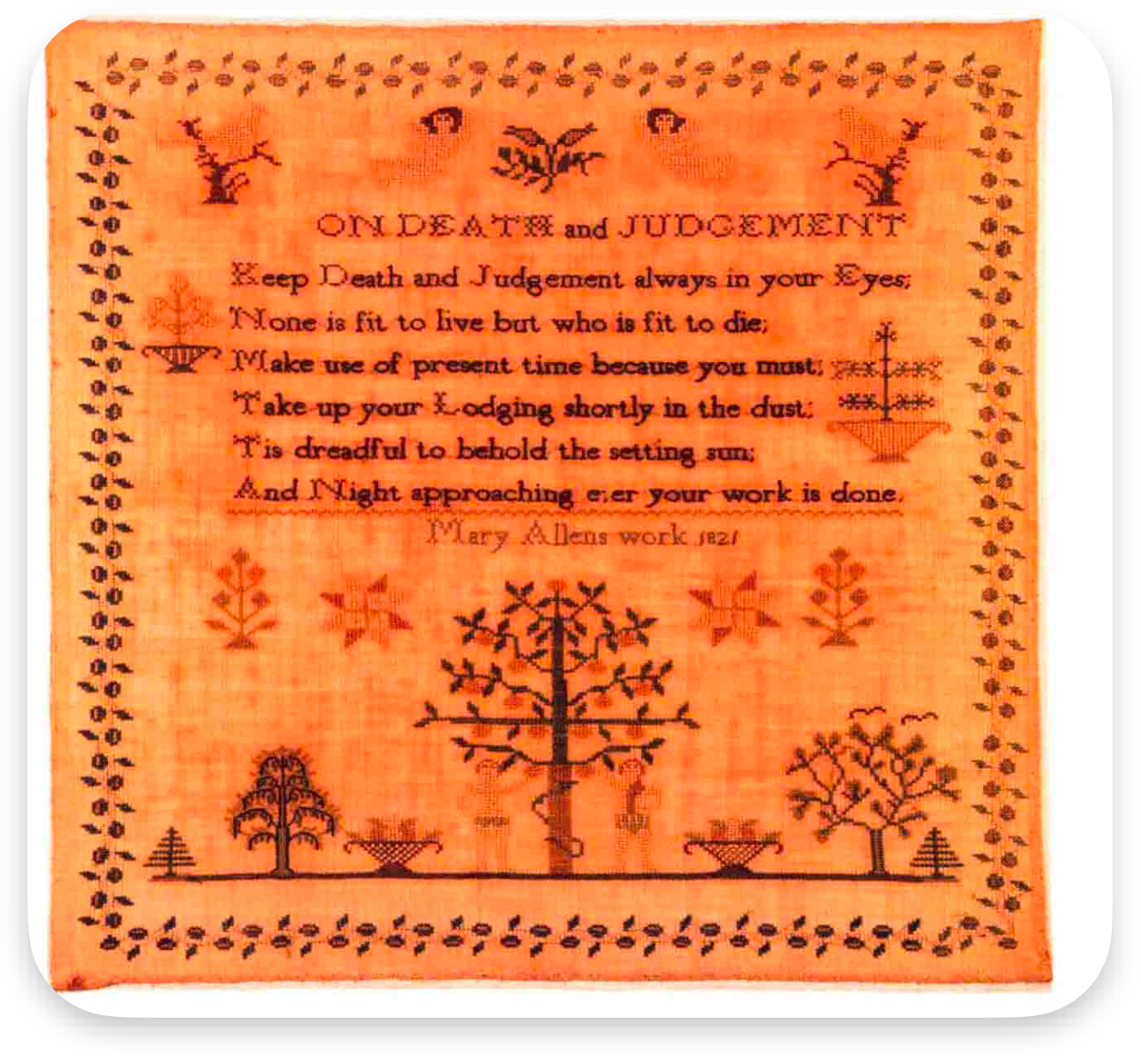

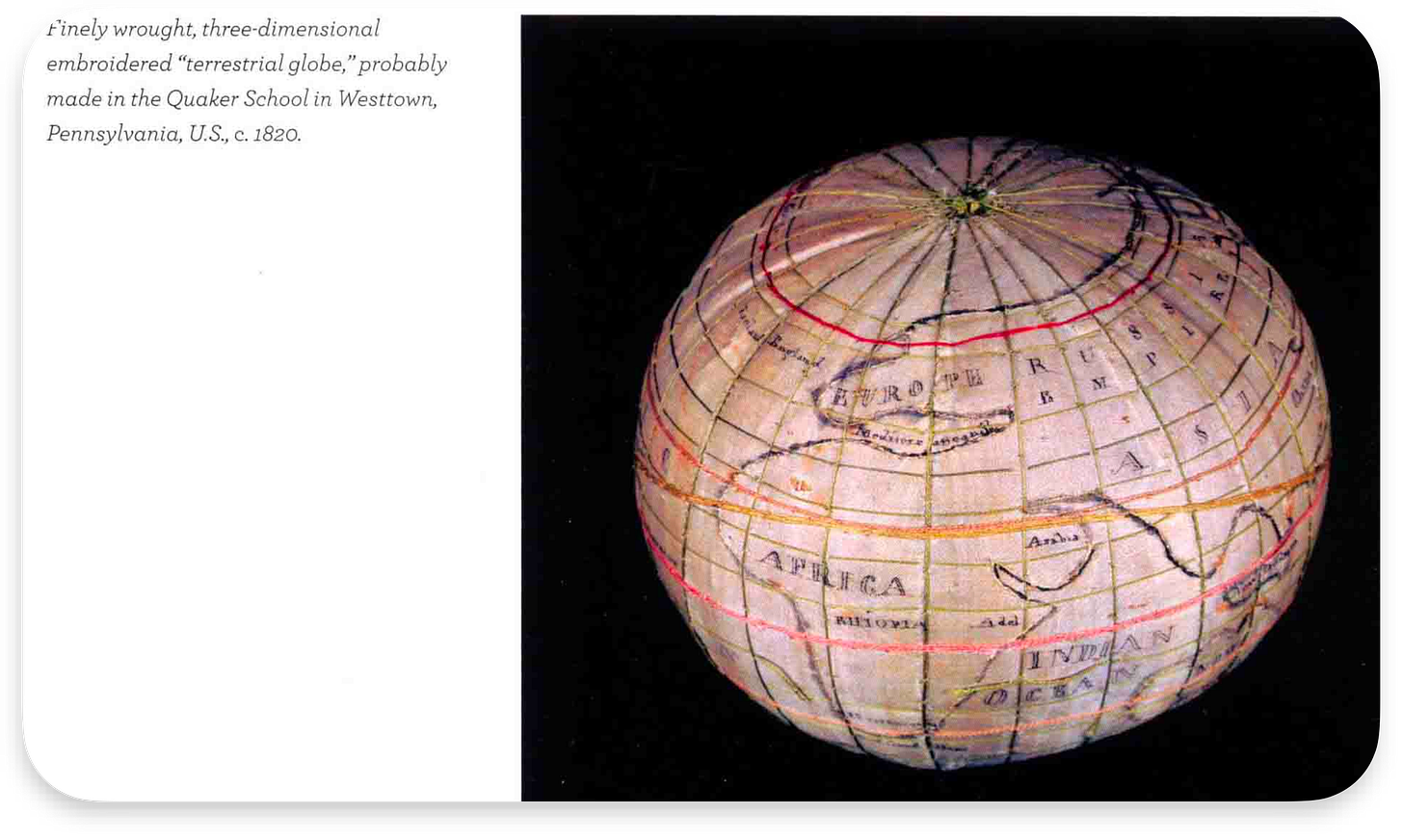

Earth-related textiles were popular during the Age of Exploration and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. As literacy rates improved in the 17th century, European girls began learning alphabets and moral principles by creating needlework samplers. Girls as young as seven were often required to embroider heavy verses about death, virtue, and family piety.

If their families were wealthy enough, they would attend aristocratic girls' schools in the late 18th to early 19th centuries, where they learned more elegant and complex embroidery techniques. Through the process of detailed embroidery "silk paintings," these girls also learned classical mythology and other content aligned with Enlightenment values.

The embroidered globes below demonstrate both needlework skills (since the globe's eight components must be cut, sewn, and stuffed perfectly to form a uniform sphere) and mastery of world knowledge. They also conveyed the message that this family was prosperous and this daughter was well-educated and refined, reflecting her education level and moral cultivation—important capital for accessing high society.

These embroidered silk paintings were typically framed and hung in family parlors after completion, just as people today hang diplomas on walls.

Around the world, there are various proverb cloths (lamba hoany) similar to European women's needlework samplers. These fabrics serve as a "universal language"—despite Madagascar having eighteen different ethnic groups with their own dialects, these cloths printed with Malagasy proverbs can be understood by people across the entire island. Women wear these fabrics throughout their adult lives.

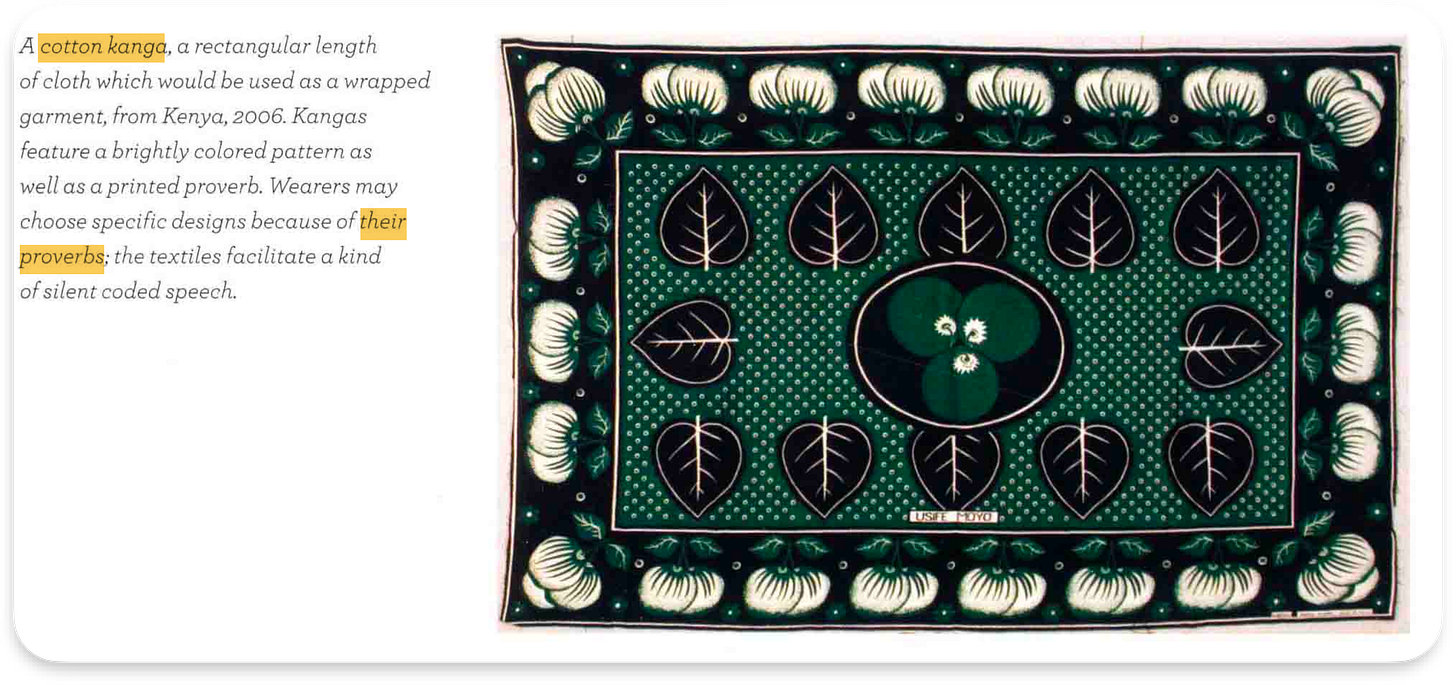

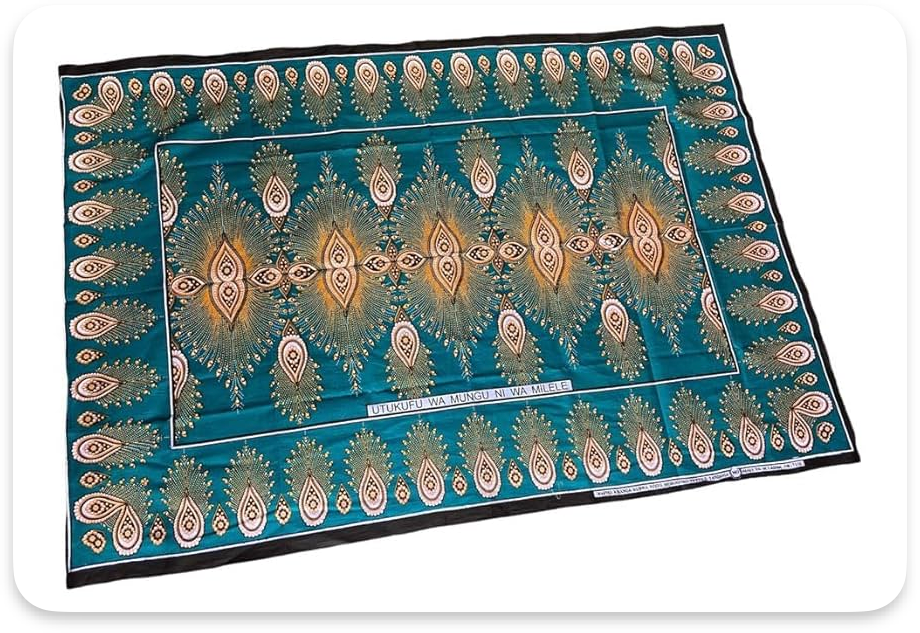

In East Africa, particularly in coastal areas of Tanzania and Kenya, Kanga is not only daily wear but also a medium for social communication and expression. Kanga typically features printed phrases or maxims, with diverse textual content including satire, puns, allegorical warnings, humorous commentary, praise, or instructional expressions. Many are quite sharp, critical, or emotionally charged.

These texts often closely follow current social contexts with strong timeliness. Like popular phrases or social commentary, they may quickly become outdated. If a woman's economic conditions allow, she typically won't wear Kanga with "outdated" phrases, as this behavior might be seen as lacking taste or inappropriate.

Interestingly, the information and "power" carried by Kanga texts don't depend on whether they can be visually read by others. Women often wear Kanga inside-out, with the printed side facing inward, or even completely reversed. But since these phrases are mostly widely circulated proverbs or fixed expressions, people can often "read" their implied meanings from the fabric's style and background even without directly seeing the text.

Fabrics printed with proverb texts and image stories are a language worn on the body, continuously expressing and "speaking" through visual symbols, cultural cognition, and collective memory, even when not read aloud, they are still "voicing."

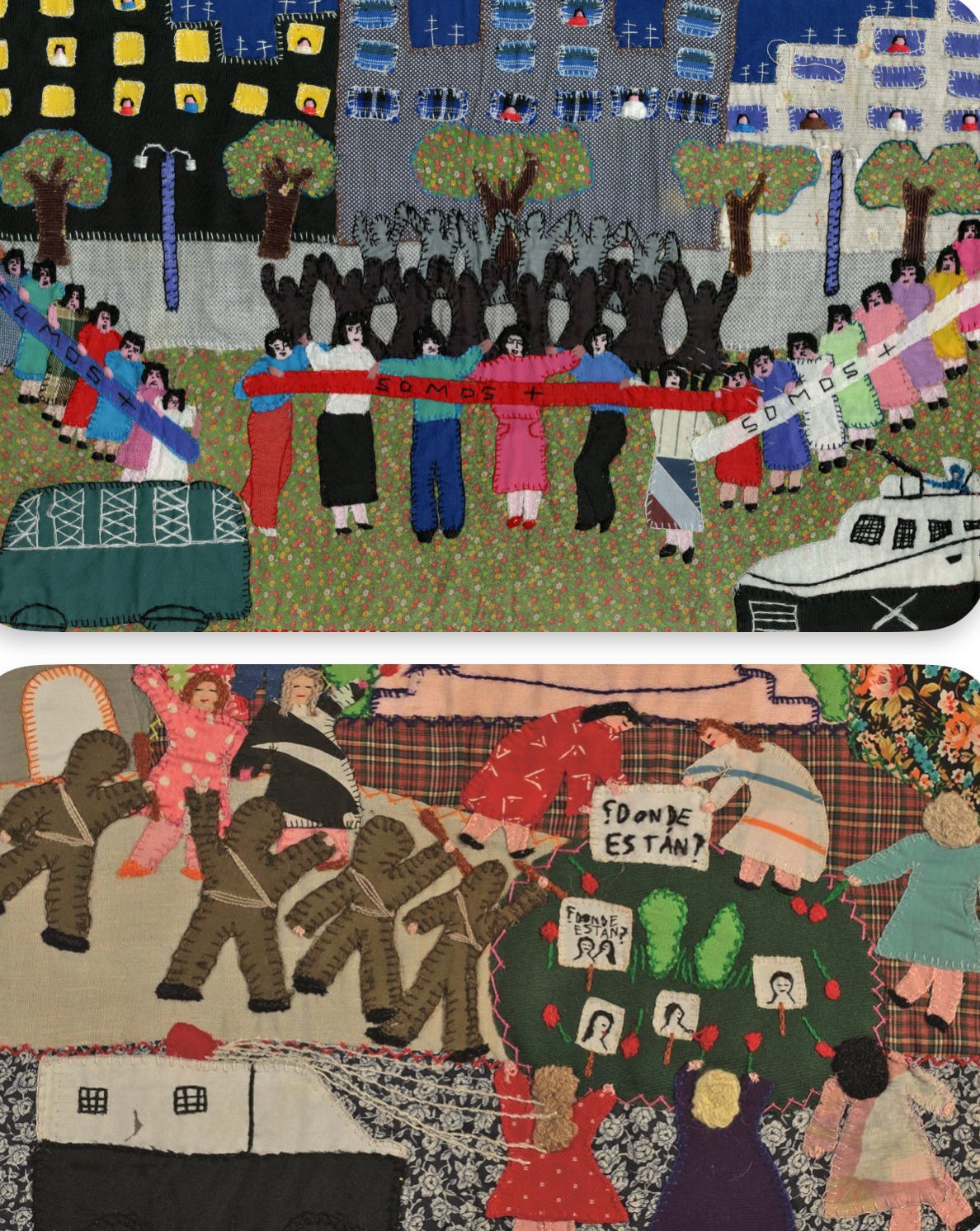

Ancient Greek tragedian Sophocles once said that textiles are "the voice of the shuttle"—even when language is stripped away, cloth can still "speak." In one of his lost plays, he told the story of Philomela: she was raped by her brother-in-law and had her tongue cut out to prevent her from telling the truth. But Philomela wove the violence she suffered into patterns on cloth, which her sister eventually read and avenged her. Weaving became her tool for resistance and voice.

Similar expressions appear in Homer's Iliad: Helen of Troy wove scenes of war and destruction into a purple cloak to express the suffering caused by herself. These mythological stories all show that even when forced into silence, people can tell stories, accuse, and convey emotions and memories through textiles.

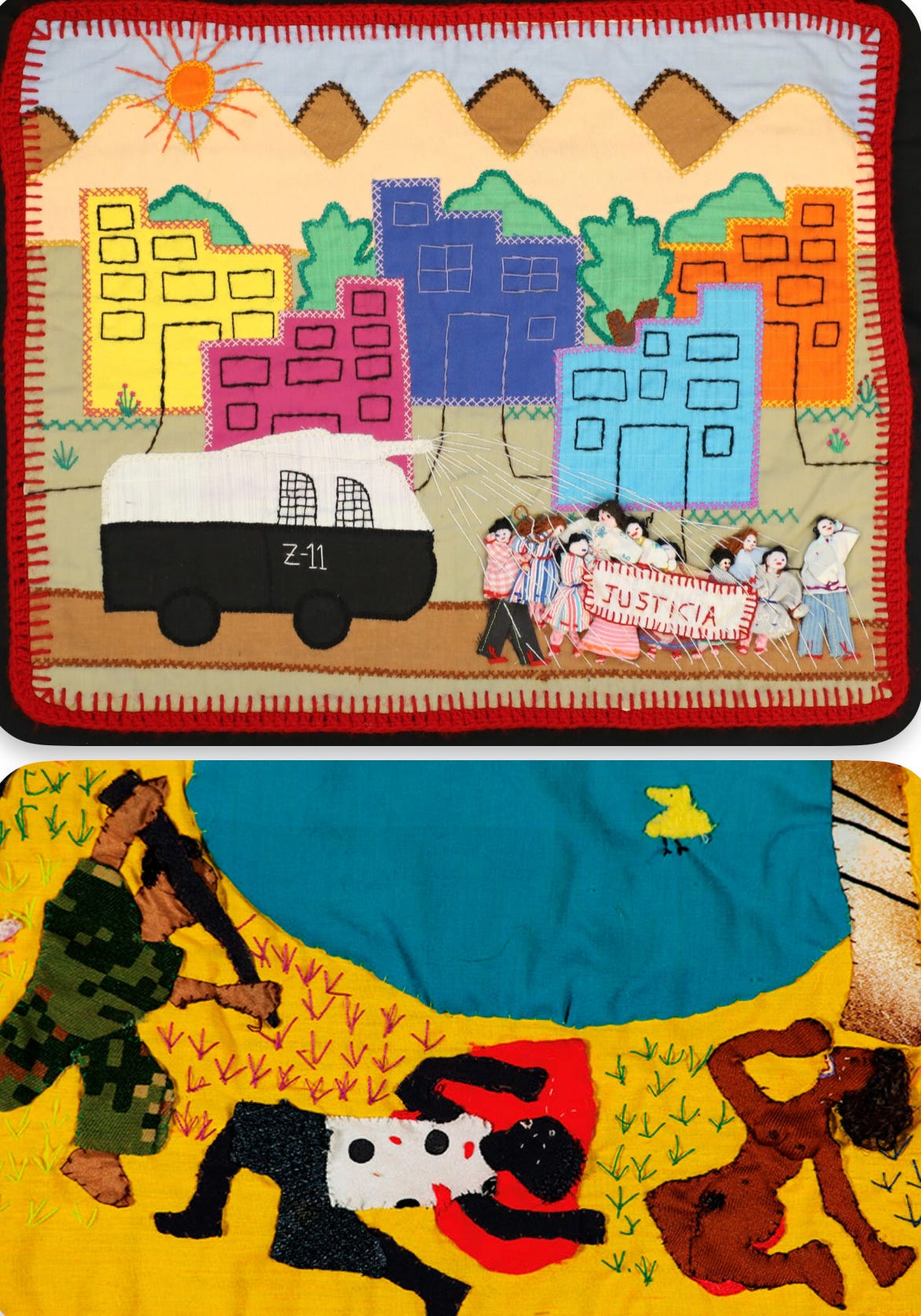

A well-known contemporary example is Chilean arpilleristas, small handmade textile works created by piecing together waste fabrics. These works not only have aesthetic value but also carry profound political significance. Especially during the 1970s-80s under the oppressive political environment of Chilean military dictator Augusto Pinochet, these patchwork paintings became tools for grassroots women to record and protest political atrocities and reveal "disappeared persons" issues.

This form of using textiles as tools for political memory and resistance also crossed borders. By the 1980s, the arpillera creation method and spirit spread to neighboring Peru, where similar "forced disappearance" problems occurred. Peruvian women began emulating the Chilean model, expressing their witness and mourning of civil war and state violence through needlework. This handicraft creation particularly flourished in Andean mountain communities, becoming a visual presentation of collective traumatic memory.

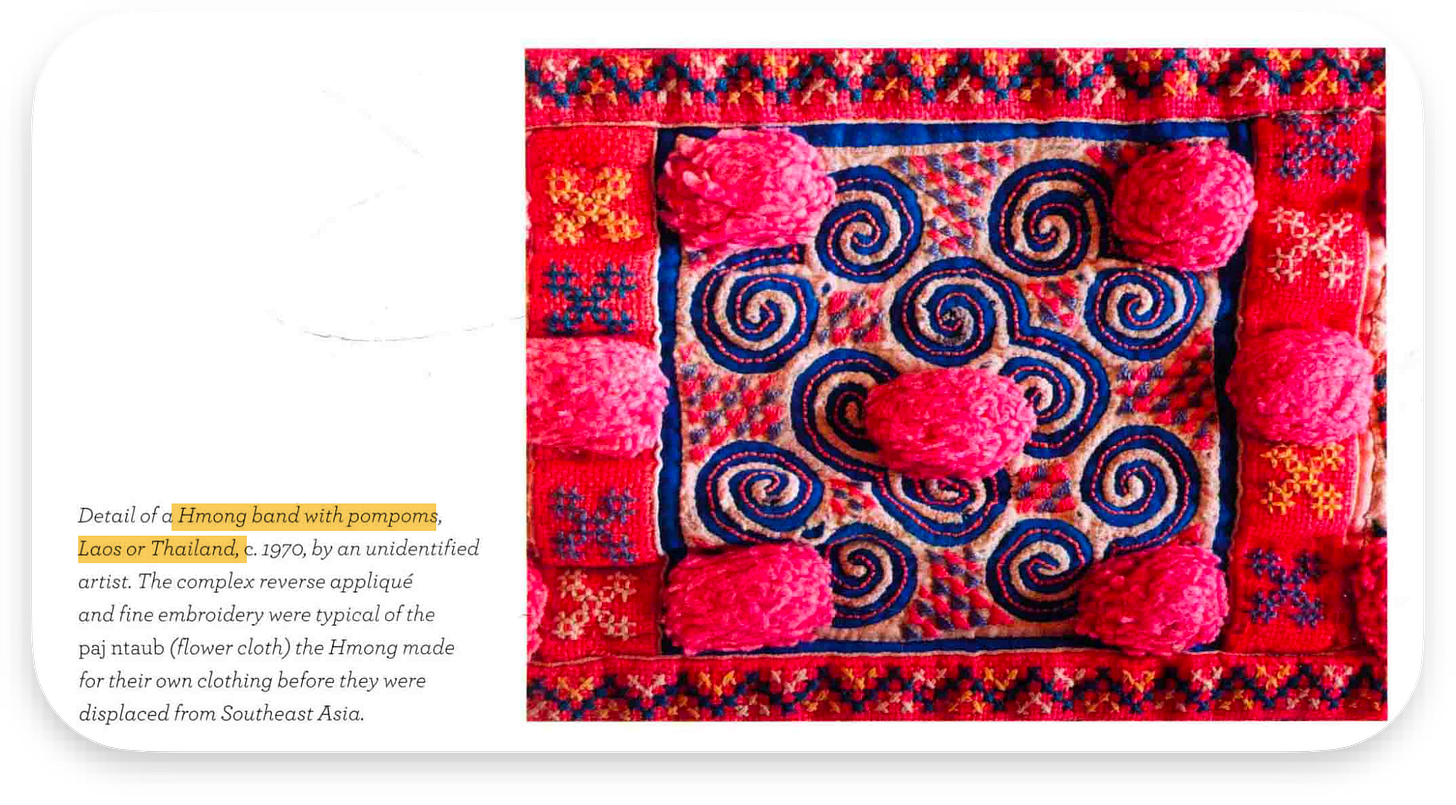

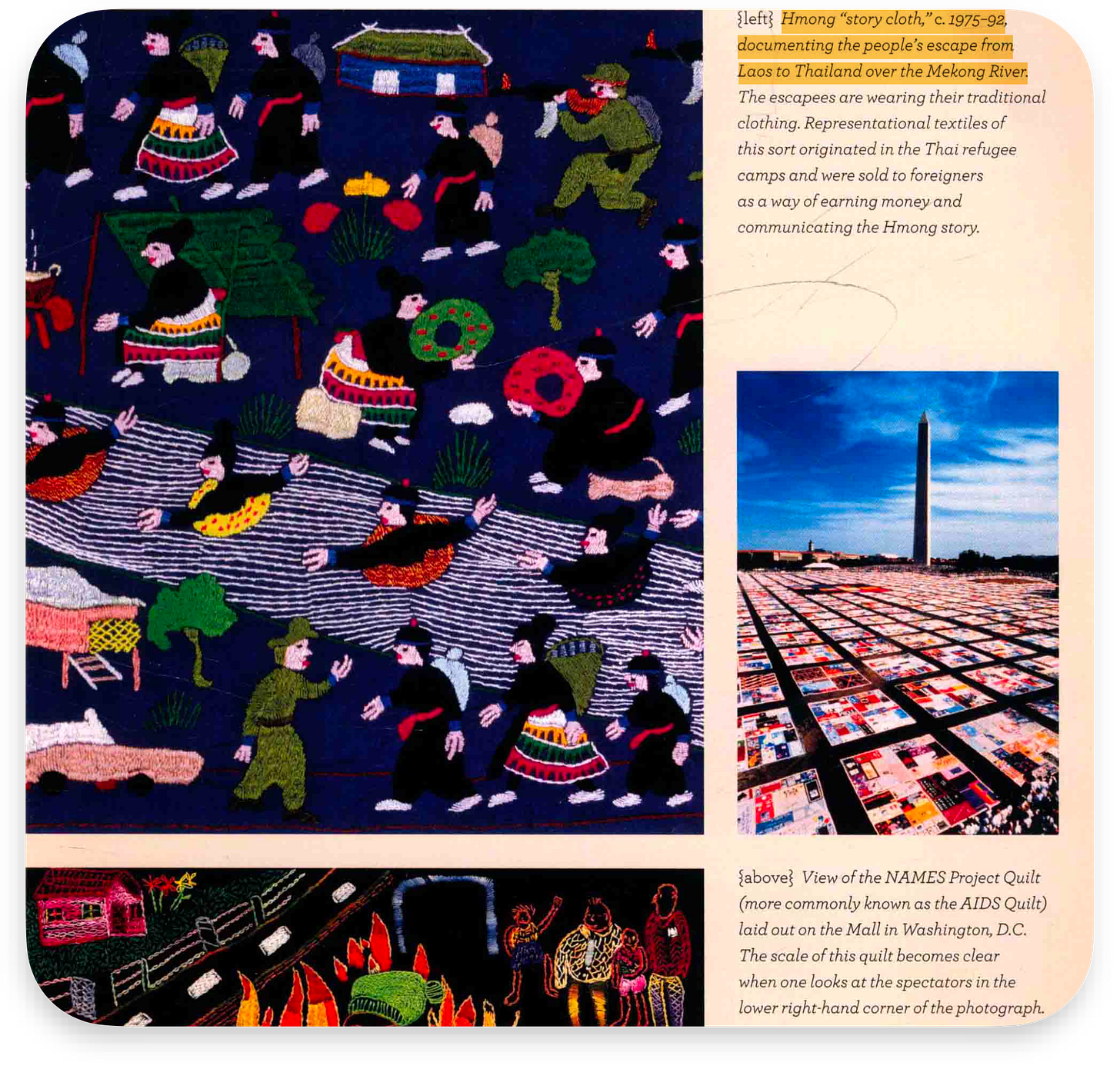

In Beverly Gordon's book, the Chinese ethnic minorities mentioned most, besides Tibetans (mainly Ladakh Tibetans from the Kashmir region of India), are the Hmong.

The Hmong migrated from Guizhou during the Qing Dynasty's policy of replacing native officials with appointed ones and after the failed Tao Xinchun uprising, moving from southwestern mountain areas to Southeast Asian mountains, no longer holding mountain songs, living in Laos and Vietnam in the lower Mekong River basin. Later serving America, after the Vietnam War failure, they moved to Minnesota, USA.

They also recorded migration and exile events as stories on textiles.

The story of the Nine-Colored Deer from China's National Museum is also displayed through images, like picture books for children.

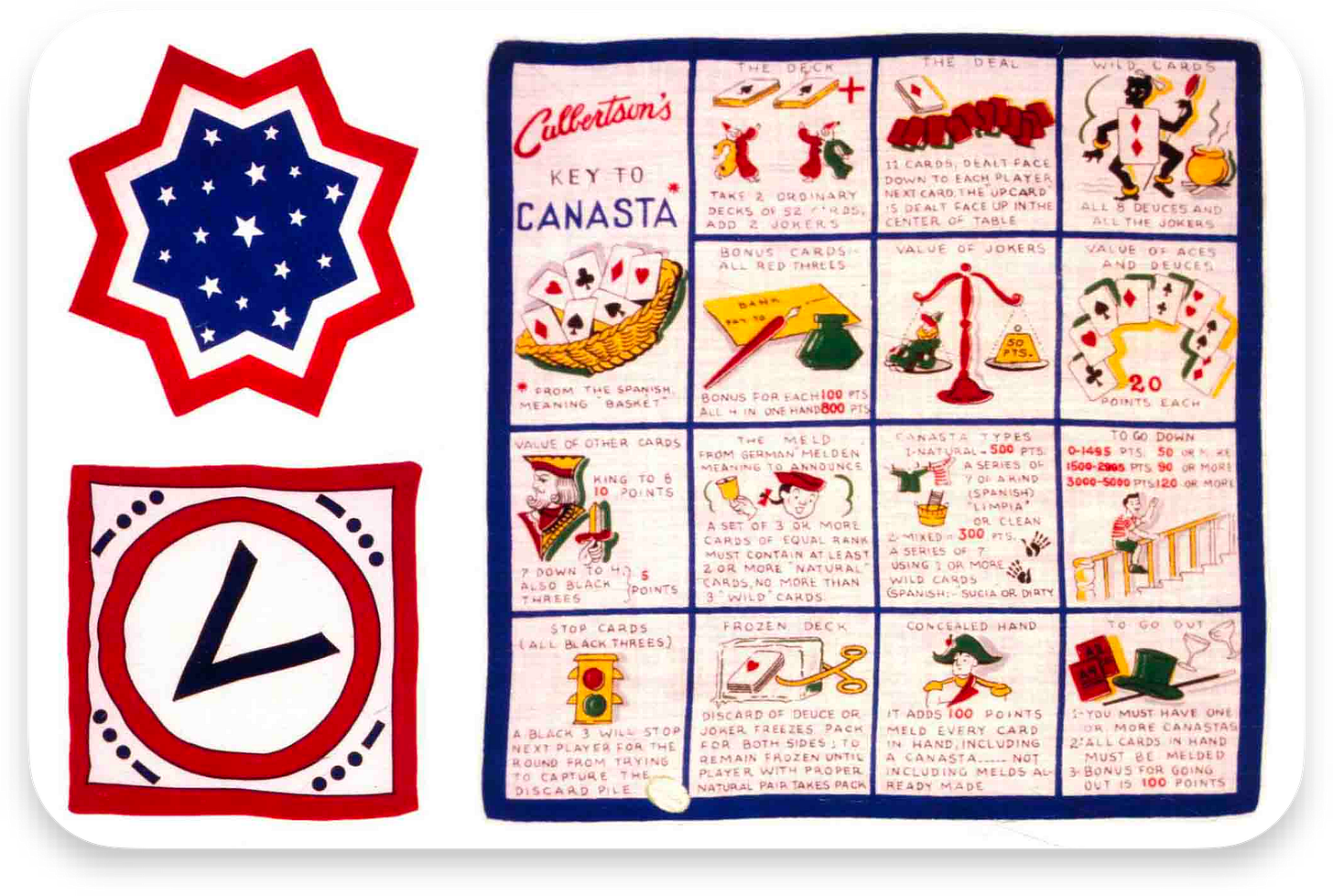

More modern examples include WWI and WWII slogan patterns.

During WWI, printed handkerchiefs were widely distributed in Britain and America. These messages were printed on silk or rayon squares, commonly worn as headscarves by women. WWII continued this tradition, with some bearing slogans like "Join the Fight," "Straight to Berlin," or "Armed Forces United"; others featured warning slogans like "Loose Lips Sink Ships" or reminders to conserve rubber and materials; still others depicted warships, tanks, or aircraft (for visual identification) or victory "V" symbols.

During the postwar economic boom, conversation prints like the one on the upper right became fashion accessories. These prints were no longer seriously commemorative but expressed current cultural hotspots or leisure activities in a lighthearted way, even presenting civic holidays in a humorous manner. America also popularized commemorative handkerchiefs themed around different states, collectible during travels, forming a collecting culture.

What I don't particularly like, besides the various rayon images from the last century, are patterns like Gingham checks below, though Scottish tartan is acceptable.

The black, white, and gray pattern below is even considered sacred cloth in Bali, called wastra poleng. It's commonly draped over guardian shrines or worn in traditional dances. A local environmental NGO once wrapped thousands of trees on the island with this cloth to prevent logging. The action was highly successful because no Balinese person dared cut down trees wrapped in this sacred cloth.

I find this somewhat incredible. From the earlier geringsing, we can see that Bali residents are somewhat too superstitious.

I also don't like Morocco's vertical striped cloth called mendil tablecloth. Any high-contrast vertical stripes or horizontal stripes like naval shirts remind me of prisons and loss of freedom, so I firmly avoid them.

Mendil cloth, like Indian Sari, Mexican rebozo, and Guatemalan tzute, has multifunctionality—it can cover bread or wine bottles, protect bridal clothes, prevent dye staining, become wrapping cloth for bundling things, or wrap babies.

Epilogue

Overall, I still prefer the simple, rustic patterns and colors of earlier times. The more modern frivolous prints and cheap machine-dyed fabrics make me feel aesthetically fatigued, even somewhat weary. In the past, not to mention those carpets and ceremonial robes decorated with gold, silver, and jewels, even traditional crafts like hand mud-dyeing, tie-dyeing, patchwork, and silk embroidery could be passed down through generations.

While today's industrially produced fabrics are cheaper, they are also more easily discarded and become waste. The current reality is that consumer powerhouses like the United States export second-hand clothing as one of their major commodities to third-world countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. This topic is also detailed in Beverly Gordon's "Textiles: The Whole Story: Uses, Meanings, Significance":

Wealthy countries face the problem of clothing surplus: clothes are cheap to buy, and the globalized fashion system constantly urges people to change their clothing to "keep up with trends." We grow tired of clothes before they actually wear out. Some people throw clothes directly into landfills, while others donate them to charities out of reluctance to waste. These charitable organizations distribute some clothing to local shelters and people in need, and sell others in thrift stores, using the proceeds to fund charitable activities. But the volume of donated clothing is so enormous that these methods alone cannot absorb it all. Today, at least half of the clothing these organizations receive is shipped overseas for resale in the thriving global second-hand market.

Continental Textile—an intermediary in the second-hand clothing export industry chain. This company collects clothing from thrift stores, carefully sorts and fumigates it, then compresses the organized clothing into standard bales for global sale. The person in charge must constantly monitor the changing preferences and demands of different national markets. (At the time, he complained that almost no market worldwide wanted cotton sweaters, and they had to throw away large quantities of such items daily.)

In Africa, different countries have their own names for second-hand clothing: in Zimbabwe it's called mupedzanhamo, meaning "the place that solves all problems"; in Nigeria it's okirika, meaning "bend-down boutique"; while Zambians call it salaula, meaning "rummaging through a pile of clothes" (image below). Tanzanians and Ghanaians use terms with more bitter connotations—meaning "dead white people's clothes."

Despite these names carrying negative connotations, the industry's growth momentum is unstoppable. A 1996 article claimed that one-third of sub-Saharan Africa's population wore second-hand clothing. In 2002, 80% of Uganda's population bought second-hand clothes, and Ghana's 2005 data exceeded 90%.

The second-hand clothing trade also creates jobs for thousands in developing countries—from truck drivers and salespeople to tailors altering clothes and workers cleaning them in markets. In 2005, Oxfam's research team in Senegal estimated that 24,000 people were active in this industry. In countries with weak local economies, unemployed workers, widows, self-funded students, and others join this field, requiring minimal startup costs to quickly generate small profits. Many family members pool resources to fund a newcomer's first 100-pound bale purchase. However, this trade devastates local textile and clothing industries. Ten years ago, Nigeria's textile industry was the largest employer in manufacturing, accounting for 25% of national employment. But jobs plummeted from 137,000 in 1997 to 57,000 in 2003, a reduction of nearly 58%. While this was also related to low-priced new clothing imports from China and elsewhere, second-hand clothing clearly played a key role.

In wealthier Saudi Arabia, second-hand clothing is also big business, worth millions of riyals annually. According to Arab News: "Every weekend, Jeddah's second-hand markets are bustling with people of different nationalities coming to hunt for bargains. You can see Filipinos, Indians, Pakistanis, Europeans, and even Americans treasure hunting here. Some buy in bulk to take back to their countries for charity donations, some buy for large families, and others serve needy groups." (Local Saudi people typically don't shop at these markets.) Some clothing that fails to sell in Jeddah is re-exported to Sudan, Somalia, and other African countries.

Second-hand clothing flowing from wealthy countries to the third world has become a global phenomenon. The United States exports large quantities of second-hand clothing to Mexico annually, despite the Mexican government's ban on domestic second-hand clothing purchases (to protect local industry). Even so, just one Texas company exports 50 million pounds of clothing annually, with large quantities smuggled across the border daily.

Of the nearly 60 clothing brands I've written about so far, I estimate about half cannot realize their value, especially the bottom 10 mid-to-low-end minimalist quiet luxury brands in the homepage brands collection, who love using synthetic fibers to reduce costs.

Under today's fast-paced "quick response" system, the consumer end sees increasingly cheap and inexpensive clothing, while the production end relies on cheap, inexpensive labor. Author Beverly Gordon also describes the factory problems brought by textiles. The next piece, "Textile Cotton: Behind the British East India Company, Triangular Trade, Civil War, and Factory Capital," will cover this topic.

pamperherself